|

(Photo credit)

I’m immortal, and I don’t think about it that much. Not because it isn’t worrisome. Being immortal is inherently worrisome, just like the alternative is worrisome. Existence in general is worrisome. But I try not to worry about being immortal, because worrying about it is futile. Trying to comprehend the eternity that stretches before me is as unavailing as trying to comprehend what comes after death. After a while, pondering existential questions with no attainable answers stops feeling philosophical and becomes tedious, self-fellating bullshit. You just have to live what’s in front of you. If it sounds like I’m just figuring that out, it’s because I sort of am. By immortal standards, I’m an infant. Disappointing, I know. I think I’d look fabulous in a toga. When it started, it was the February fourteenth of 1945. An American plane was hit in the engine by Japanese fire, fell from the slate gray sky like a shooting star. Its blazing red reflection ignited the swell of colorless water. And then it was gone, taking with it all the color in the world. In that plane was my fellow air force pilot. The love of my life. You. I know what you’re thinking: you weren’t alive in ‘45, and you weren’t a man. Well, I’m gonna tell you you’re wrong on both counts. You’ve been a man before. You’ll be one again. It doesn’t matter to me, so long as it’s you. And let me tell you, sweetheart, you don’t know what love is, ‘till you fall in love in the World War II air force. Every passing touch is cherished, every moment together, a fleeting eternity. It was all very Spartan. I reminded myself every minute of every day that I could lose you, tried to operate under the assumption that I would. I thought that might lessen the pain of it. Which, I can cheerfully report, it didn’t. At all. After you died, the world stayed as cold and colorless as the ocean that swallowed you. The war ended, and I couldn’t bring myself to care. I came home to parades and streamers and cheering crowds, and all I could think was, He’s dead. He’s dead, and I’m alive. How horribly wrong is that? So I decided to fix it. I got myself up on a good, tall chair, I put a noose around my neck, and I jumped. Dangled there for a good, long while, looking around my shitty little hotel room and saying goodbye to my life. To my father, probably still drinking himself to death and kicking his dog back in Illinois. To my mother, wherever she was. Hopefully happy, and with a fellow who treated her right. Even though she left me with him. To the apology note taped to my pillow, addressed to whatever poor maid would find me. The fifty cent tip for her troubles. To the radio I forgot to turn off, to the Singing Weather Girl giving me a badly rhyming, probably inaccurate forecast for snow. To the dust in the air, ignited by sunlight. Was that all any of us were? My list of goodbyes got impressively long before I realized something hinky was going on. Namely, I wasn’t dying. In a more mentally sound state, I might have wondered how I could still be alive after about twenty minutes without any oxygen. At the time, I was mostly upset. For a suicidal person, not dying is very upsetting. After I figured out how to get myself down – which was no picnic, I’ll tell you – I got my sidearm, and I ate a bullet. That seemed to do the trick. Then I woke up the next morning in a pool of my own dried blood, with the hole in the back of my head already scabbed over. You’ve gotta wonder, what did the other hotel guests think about the gunshot? Was that, like, a regular occurance in those parts? But anyway, that’s how I figured I couldn’t die. I don’t think I’d aged for a while, either. Dug up a picture from about six years back of when I was nineteen, and I looked pretty much the same. Which reminds me, I brought a little something. You see this fellow? Handsome guy, right? It’s sort of a bad picture, but yeah, that’s me. Back in ‘39. I still dress the same way, too. You always made fun of me for that, didn’t you? Said I should’ve been a 1940s television announcer. You weren’t too far off. Anyway, without the option of dying, I had no choice but to live. Well. Survive, more like. I got a job as a paper pusher, which I hated more than life itself. I got an apartment. A house. Houses were easier to get back then. Tried not to get attached to anyone, so I wouldn’t have to watch them get old and die. I know everyone wants to feel safe. But none of them realize that there is no greater loneliness than being safe from death. The days went slowly. They’re always the slowest without you. To pass the time, I did a lot of real deep thinking about what it meant to be immortal. Like, could my brain comprehend eternity? Would I go insane? If the universe came to an end, would I live on? What if the earth got hit by a meteor? What if I flew into the sun? Thinking about it let me pretend I had some sort of control over it. The days went slowly, but the years went fast, and suddenly I woke up and it was 1960. Around that time, I realized I should probably do something with my never-ending life. There were a couple reasons for that. For one thing, I’d been a working the same job and living in the same house for fifteen years, and I realized someone would probably figure out I wasn’t aging. Report me to the government or something. Next, people were talking about the Vietnam War, and I got this irrational fear I might be drafted. Even though I was, on record, forty-five, and too old to register for draft. But I didn’t want to take any chances. I can’t think of anything worse than watching countless good men die, equipped with the knowledge that I will survive, and coming home without a scratch on me. I still have nightmares from the first time around. So, I moved across the country, and I enrolled in college for pre-med. I always wanted to be a doctor, anyway, before – well, everything. It was hard work, especially considering I had a sixth grade education. But I wanted to do it right this time. If I had to exist, I wanted my existence to mean something. Because, really, how many people died while I lived? How many people are dying now? An unwanted gift is still a gift, and it felt wrong to just sit on it with my thumbs up my ass. Late that May, I walked out of a final exam. The first really warm day of the year. Everywhere I looked there were colors, daffodils and tulips and hyacinths, exploding out of the ground like fireworks. Bees humming like little helicopters. Something was different that day. The world was alive again. That’s when I saw you. You were this tiny little thing, in a little pink dress, one of those warm weather honeys. Fat little blond curls. You looked like Shirley Temple’s big sister. You couldn’t have been more different from the big, angry man I fell in love with, but – it was you. I can’t explain it. My soul could see something that my eyes couldn’t, and it recognized you. You noticed me staring, and you looked at me like I was an old friend. Like you’d seen me before, but couldn’t work figure when or where. Then you rounded the corner of the cafeteria, out of sight. The wind was knocked out of my lungs by the time I chased you down, even though you weren’t five yards away. My heart was a jackhammer. I could barely manage a hello by the time I caught you. You tilted your head to the side and your eyebrows scrunched together and you said, Do I know you? It was all so you, I wanted to cry. Your words in a different voice. Your soul behind different eyes. I wanted to hug you, to fall to my knees holding you, to sob and blubber about how much I missed you. You, the only person who had ever truly loved me. You, the love of my life. You. You. You. Instead, I pulled myself together and said, I’m sorry, I saw you walking and I just had to talk to you. Which wasn’t a lie. And then I asked if you’d like to get coffee some afternoon. And you said, How about this afternoon? And so we did. That was your second life. Your reincarnation. How do I know? Well, I later found out you’d been born nine months after your plane went down. And you had that little birthmark. Yeah, you know the one. You always have that little birthmark. It’s always in the same place, God bless. But more than anything, like I said, I just recognized you. It’s as simple as that, and as complicated as that. You brought me to life again. I’d wake up in the morning grateful to be alive, even with the knowledge that I would be alive a little longer than I found optimal. We moved in together my sophomore year, and you filled my house and my heart with warmth and the smell of roses. You were, obviously, a woman, which took some getting used to. But it had its benefits. I could pick you up, carry you more easily than before. You were a lot more vocal about your feelings, and you laughed a lot, as girls are generally encouraged to do. It was nice to see that. You never laughed enough before. And I could hold you, hold your hand, kiss you, anywhere. Take you dancing. No one even spared us a glance, except to smile at us. I could never get over that. The day of our graduation, we got engaged. We took a few photos of that day. Here, I, uh – yeah. Yeah, that’s you, with the little bow in your hair. My beautiful girl. June of ‘64. Look how happy we were. I said to you that night, as I kissed my way down your chest, I don’t know if there’s a Heaven, but this must be what it’s like. Not two weeks later, you died again. Not falling from the sky in a blaze of glory, but hit by a drunk driver leaving the grocery store. I don’t even know how I processed that. My mind was a screaming wall of static, incapable of thought. I couldn’t reconcile that this could happen. You were supposed to be safe. This was supposed to be your good life, your long life, your happy life, to make up for the short, shitty, painful life you had before. And here I was, alive, while you were dead. Again. I got this idea that I might sit in the ocean for a hundred years. That seemed reasonable at the time. I only lasted about a week, ‘cause I kept thinking about eels. It gave me a bit of time to think, though, and I realized something that should have been sort of obvious: I might find you again. Or rather, you might find me. So I should probably be there waiting for you. And I did. For another two decades, I waited. That makes me sound sort of useless, so I’ll clarify that I went to medical school. Around that point, I started to realize that pain is a non-negotiable part of life, and that trying to avoid it was never the point of living. So I really didn’t have any excuse to avoid making friends. And anyway, it’s a shitty excuse, not forming connections with people because they’re going to die. That’s like never reading any books because you know they’re going to end. Even though you weren’t there at the time, I think I owed that to you. Those four years we spent together showed me the joy of finitude. They taught me to stop fearing being happy, just because someday I might not be. Which brings me to your third life. Can’t really tell you about that one. You see, that time, I found you in the AIDS ward. You’d had a tough life. Tougher even than when you were in the air force, which is really saying something. You were in the final stages, right before the virus took you. I won’t go into the details. I promised you I wouldn’t. I wouldn’t want to. That was the hardest, seeing you like that. It was hard for me, but, I had to keep reminding myself, it was harder for you. What I was going through was nothing compared to your pain. I took care of you, and I visited you every day. You were skeptical, not used to people being nice to you just for the hell of it, but some part of you recognized me. Just the way you did before. It was still you in there. Undeniably you. I could never decide if that relieved the pain or made it worse. Eventually, a few weeks before the end, I told you. For the first time, I told you. About what I am. About our lives together. I didn’t want you to be afraid to let go. You didn’t believe me, which was to be expected. Thought I was crazy or making fun of you. So the next day I came back and fired a nail gun into my head. Then you believed me. The next thing you said to me was, When we find each other again, you can’t tell me I was ever like this. And I tried to argue, but you insisted you wanted to forget. And then you said you wanted me to forget, too. So I won’t. I won’t tell you about that life. Just know, I loved you then, every bit as much as I love you now. Every bit as much as I’ll always love you. I realize now how ashamed you were, and I wish I’d had the sense to tell you you didn’t have to be. No amount of suffering could ever make you less beautiful to me. You died, and I got through it because – well, I got through it, because I really didn’t have much choice except to get through it. And I just kept clinging to the belief that I’d find you again, that we’d find each other again. That your next life would be better. I was getting better at the whole grief thing. The first time I lost you, I plunged into suicidal depression for fifteen years. And that grief was still there. It still is. But though the grief lives in me, I no longer live in grief. And I knew I’d find you again. Now, the nineties. The nineties were interesting. For one thing, I got recruited by the I.S.I., or International Society of Immortals. Yes, that’s a thing. Everyone babies me a little, because I’m the only immortal in the I.S.I. who’s younger than three hundred. It’s really sort of patronizing. But there are some big names: Keanu Reeves, a.k.a. Paul Mounet, a.k.a. Charlemagne. Tommy Wiseau. Weird Al. Lucy Liu. Oscar Isaac. Cher. A whole bunch of others who I’m probably forgetting. Immortality isn’t too rare an affliction. Some of them went the Twilight Zone route, with a Faustian Bargain or a genie. Some of them are vampires or witches. Others, like me, were just born this way. Either way, it’s nice to know I’m not alone in eternity. I learned some good tips on faking your death and changing your identity, which I decided it was probably time to do. I mean, I’d been working at the same hospital for about twenty years, with no signs of aging except some fake reading glasses and a touch of gray hair coloring around the temples. So, I did the reasonable thing: I fell out a tenth story window. It’s weirdly cathartic, falling out a window. I highly recommend it. The I.S.I. supplied the fake body for my funeral. Got me a fake birth certificate, fake bachelor’s degree, fake social security number. Even some fake family photos. Everything I’d need for my new, fake identity. I relocated here with that fake new identity to start a real, new life. Started a real Ph.D. in psychology. Found you. The real you. I don’t know if everyone gets reincarnated, but I believe everyone has a soul. I believe our souls are drawn together, like the ocean towards a full moon. And I believe we’ll always find each other, as surely as the tides. It’s not an accident that I took you travelling so much, that I bought you so many gifts. Experience has taught me how short life can feel, and how fragile it can be. I wanted to make it great for you. Did I do a good job? I hope I did. At the very least, you always seemed happy. I know I was happy. This has been the best one yet, and the longest. Ten years together ain’t bad, all things considered. And cancer, believe or not, isn’t the worst way I’ve seen you go. Is that callous? Yeah, that’s probably callous. I’m sorry. Immortality can make people a bit insensitive, even if we’re really not trying to be. But hopefully you’ll forgive me by the time you’re born again. Anyway, it’s worth waiting for, even if it never lasts long. You always seem to die so young. But what in life is meant to last long? We’re all dust, set ablaze by the sun. A life of any duration is a miraculous event. I’m telling you this, my heart, my darling, because I don’t want you to be afraid. I want you to understand that it’s okay to let go. Go to sleep, my darling. My ocean. I’ll find you when you wake up.

2 Comments

1. Ask yourself these basic questions:

Brainstorm random questions about your characters, their likes, dislikes, et cetera. Here are examples:

Simple character sheets are a great way to fill in the gaps and get to know your character. Though there are quite a few floating around on my favorite blogs, but here are a few examples:

Of course, the only way to truly get to know your character is to write about them. You never know how they’ll develop until you get going, and once you do, they’ll never cease to surprise you. Characters truly do gain lives of their own, so don’t give up and keep writing. And in the meantime, I hope this helps! <3 You may have heard that titles don’t matter, and that they won’t make or break your career. Whoever told you that is either grievously uninformed or a filthy liar.

A title must do the following:

Like cover art, your title can determine whether or not anyone will actually read your book. Also like cover art, you probably shouldn’t name it like a twelve-year-old with a DeviantArt account. But how do you check off such an extensive yet vital list of criteria? Well, being the magnanimous individual that I am, I’ll tell you. Let’s take a short journey through five of my personal favorite approaches: 1. Use metaphor. Some of the most memorable and iconic titles are derived from metaphor, allegory, and simile. If you have a metaphor that encapsulates your book’s theme or tone, consider using it for your title. When done correctly, these will also provoke interest from prospective readers, as they will have to read your book to put the metaphor into context. Examples: The Catcher in the Rye, by J.D. Salinger Life of Pi, Yann Martel A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, Betty Smith 100 Years of Solitude, Gabriel García Márquez Of Mice and Men, John Steinbeck To Kill a Mockingbird, Harper Lee Lord of the Flies, William Golding 2. Ask a question. Is there a fundamental question your book is asking? (There probably should be, but that’s a topic for another day.) If so, consider presenting it to the reader from the get-go. These questions can be existential or personal, metaphorical or literal. But they should make the reader want to know the answer. Note that you can get creative about this. A question doesn’t have to be one you ask the reader, but one you provoke the reader to ask themselves. Like, “Did this author really spoil the ending with their title? I’ll have to read and find out!” As you’ll see in the titles below. Examples: Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? by Philip K. Dick Are You There, God? It’s Me, Margaret, by Judy Bloom Where’d You Go, Bernadette? by Maria Semple Skippy Dies, by Paul Murray John Dies at the End, by David Wong 3. Invoke a character’s voice. Ask yourself how your protagonist or viewpoint character would choose to title their story. Ask yourself who this person is. Are they an angsty teen? A plucky optimist? Self-conscious? Ironic? Morose? Sassy? Your viewpoint character should essentially control the tone of your novel, and the title should be reflective of such. Examples: My Big Nose and Other Natural Disasters, by Sydney Salter Everything I Never Told You, by Celeste Ng Is Everyone Hanging Out Without Me? (And Other Concerns), by Mindy Kaling Never Let Me Go, Kazuo Ishiguro 4. Utilize the setting, or a memorable place, object, or event. Is there a place, object, or event at the heart of your story? Maybe its a restaurant that is to your ensemble what the Central Perk is to the cast of Friends, a stuffed animal or piece of jewelry that serves as the story’s MacGuffin, a book that holds the secrets to the protagonist’s identity. Or maybe it just, for one reason or another, perfectly encapsulates the tone and philosophy of your story. I seem to be partial to this one, because it’s how I chose to name three of my novels: An Optimist’s Guide to the Afterlife (named after a book handed out to the recently deceased), General Tso’s Chicken From Outer Space (named after a Chinese food restaurant in a UFO hotspot town), and Diner at the End of the World (named after a diner frequented by Eldritch Horrors.) Examples: ‘Salem’s Lot, by Stephen King The Road, by Cormac McCarthy The Restaurant at the End of the Universe, by Douglas Adams Jurassic Park, by Michael Crichton Good Omens, by Neil Gaiman and Terry Pratchett The Lord of the Rings, by J.R.R. Tolkien 5. Introduce the protagonists (but get creative about it.) In ye olden times, an opulence of great literature popped up that was named after specific characters. Think Anna Karenina, Oliver Twist, David Copperfield, Don Quixote, The Great Gatsby, and Jane Eyre. You can still do this–lots of authors still do, and it works great if you have a particular cool or quirky name–but in an already saturated market, it’s probably a good idea to put a twist on it. I’ve observed three ways to go about this. First, you can introduce the main character and major conflict/theme of your story. Examples: Simon Vs. the Homo Sapiens Agenda, by Becky Albertalli Aristotle and Dante Discover the Secrets of the Universe, by Benjamin Alire Sáenz The Miseducation of Cameron Post, Emily M. Danforth Approach number two: introduce the readers to the group of people your story is about. Examples: The Help, by Kathryn Stockett American Gods, by Neil Gaiman The Twelve Tribes of Hattie, by Ayana Mathis The Vacationers, by Emma Straus Crazy Rich Asians, by Kevin Kwan And approche trois, name the title of a main character, particularly if it’s memorable and plays a large part in the story. Examples: The Giver, by Lois Lowry The Obituary Writer, by Ann Hood The Beekeeper’s Apprentice, by Laurie R. King The Hobbit, by J.R.R. Tolkien The Martian, by Andy Weir These are just a few of my favorite methods of naming stories! To my followers, I invite you to add more, and to share your own favorite titles. Other sources: How to Come Up With the Perfect Title For Your Novel How to Choose Your Novel’s Title: Let Me Count 5 Ways 7 Tips to Land the Perfect Title For Your Novel How to Find Good Titles For Your Novel How to Name Your First Novel How to Title Your Novel I hope this helps, and happy writing! <3 1. Allow the dialogue to show the character’s personality.

If you really think about your conversations, it can be telling exactly how much of someone’s personality can shine through when they speak. Allow your character’s persona, values, and disposition to spill over when they speak, and it will make for a significantly more interesting read for you and your reader. For example: let’s take a look at a mundane exchange, and see how it can be spruced up by injecting it with a good dose of personality. Exhibit A) “How was your day, by the way?” asked Oscar, pouring himself a drink. “Not too bad,” replied Byron. “Cloudy, but warm. Not too many people.” “That’s nice.” Exhibit B) “How was your day, by the way?” asked Oscar, pouring himself a drink. “Ugh. Not too bad,” groaned Byron, draping himself on the couch. “Warm, but dreary. Gray clouds as far as the eye could see. Not anyone worth mentioning out this time of year.” A pause. “Well, except me, of course.” “Hmmph,” said Oscar, glancing over his shoulder. “If it were me, I wouldn’t want it any other way.” Isn’t that better? Already, the audience will feel as though they’ve gotten to know these characters. This works for longer dialogue, too: allow the character’s personal beliefs, life philosophy, and generally disposition to dictate how they talk, and your readers will thank you. Of course, this example is also good for giving the reader a general sense of what the characters’ relationship is like. Which brings me to my next point: 2. Allow the dialogue to show the character’s relationship. Everyone is a slightly different person depending on who they’re around. Dynamic is an important thing to master, and when you nail it between two characters, sparks can fly. Work out which character assumes more of the Straight Man role, and which is quicker to go for lowbrow humor. Think of who’s the more analytical of the two and who’s the more impulse driven. Who would be the “bad cop” if the situation called for it. Then, allow for this to show in your dialogue, and it will immediately become infinitely more entertaining. Example: “Alright,” said Fogg, examining the map before him. “Thus far, we’ve worked out how we’re going to get in through the ventilation system, and meet up in the office above the volt. Then, we’re cleared to start drilling.” Passepartout grinned. “That’s what she said.” “Oh, for the love of God – REALLY, Jean. Really!? We are PLANNING a goddamn bank robbery!” Some more questions about dynamic to ask yourself before writing dialogue:

3. Think about what this dialogue can tell the reader. It’s better to fill the reader in more gradually than to waist your valuable first chapter on needless exposition, and dialogue is a great way to do it. Think about what your characters are saying, and think about ways in which you can “sneak in” details about their past, their families, and where they came from into the discussion. For example, you could say: Tuckerfield was a happy-go-lucky Southern guy with domineering parents, and bore everyone to death. Or you could have him say: “Sheesh. All this sneakin’ around in the woods late at night reminds me of being back in Kansas. Good times, man, good times.” There was a pause, before he added, “‘Course, it wasn’t nearly so fun when I came home late for curfew and had to sleep on the front step, but y’know. Life happens.” Isn’t that much better than the omnipresent monotone? Dialogue is also a great way to fill in potential plot holes early on, by having your characters talk them out and explain them. Moreover, dialogue can also be used to foreshadow, offer relevant hints about the climax, or provide information necessary for the resolution. So use it wisely! 4. Sprinkle in mini-actions throughout. Even in actionless dialogue, no one actually does nothing. In my case, for example, I stim a lot. I play with my hair. I play with eating utensils. It’s probably very annoying for those around me, but you get the point. Less fidget-y folks might not do this as much, but they rarely sit totally still during conversations, either. So occasionally add in these mini-actions, and it will make your characters feel a bit less like disembodied voices or floating heads. For instance: Jo leaned back in her chair rolling her stiff neck from sitting still for so long. “…So the way I see it,” she continued. “Even if Pheris Beuller’s Day Off didn’t take place in Cameron’s imagination, Pheris was clearly a sociopath whose behavior shouldn’t be glamorized.” “Ha. As if.” Avery paused to sip her root beer. “Pheris,” she began, raising an index finger. “Was clearly emblematic of counterculturist movements such as the Beat Generation, and his disregard for the capitalistic dogmas imposed upon younger generations is something to be admired.” “For Christ’s sake, will you two lighten up?” scoffed Leo, counting out bills for the pizza. “We were talking about which movie we wanted to watch tonight. Jesus.” 5. Remember how people actually speak. In real life conversations, people don’t speak in paragraphs. Alright, some people might, and this can actually be interesting as the personality aspect of a certain type of character. But generally speaking, people don’t speak in paragraphs, or as though they’re writing thought-out prose or letters. In real conversations, people stutter. They laugh at their own jokes, repeat words or phrases, and lose their train of thought. Naturally, you don’t have to illustrate in your writing exactly how chaotic and mundane human speech can be, as writing would be pretty boring in general if it was strictly limited to miming reality. But it’s good to keep in mind that your characters are talking, not writing in purple prose. Exhibit A: “When I was a young boy, my mother and I had a most tumultuous relationship,” said Marcus. “She saw me as a hallmark of her past failures, and took every opportunity to remind me as such.” Exhibit B: “My mom, when I was kid, we had what you’d call a sort oftumultuous relationship,” said Marcus. “Nothing I ever did was right for her. She, uh – I think she saw me as sort of a hallmark of her past failures. Took every opportunity to remind me of that.” Which of these is more organic, more easy to visualize, and more telling of character? Unless the point of this dialogue is to illustrate that Marcus is a gentleman crook of some kind with pristine speaking mannerisms, I’m going to say the latter. Best of luck, and happy writing! <3 |

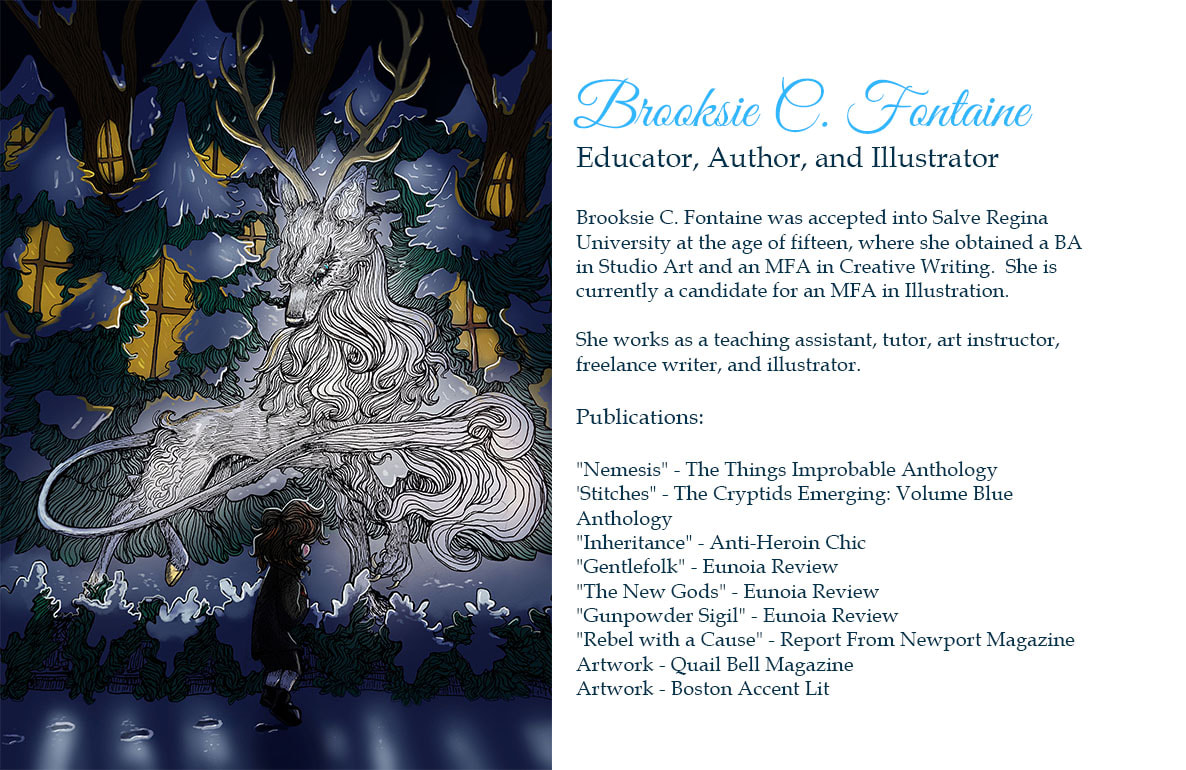

About the AuthorBrooksie C. Fontaine was accepted into college at fifteen and graduate school at nineteen. She has an MFA in English, and is currently completing a second MFA in Illustration. Archives

March 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed