|

1. Allow the dialogue to show the character’s personality.

If you really think about your conversations, it can be telling exactly how much of someone’s personality can shine through when they speak. Allow your character’s persona, values, and disposition to spill over when they speak, and it will make for a significantly more interesting read for you and your reader. For example: let’s take a look at a mundane exchange, and see how it can be spruced up by injecting it with a good dose of personality. Exhibit A) “How was your day, by the way?” asked Oscar, pouring himself a drink. “Not too bad,” replied Byron. “Cloudy, but warm. Not too many people.” “That’s nice.” Exhibit B) “How was your day, by the way?” asked Oscar, pouring himself a drink. “Ugh. Not too bad,” groaned Byron, draping himself on the couch. “Warm, but dreary. Gray clouds as far as the eye could see. Not anyone worth mentioning out this time of year.” A pause. “Well, except me, of course.” “Hmmph,” said Oscar, glancing over his shoulder. “If it were me, I wouldn’t want it any other way.” Isn’t that better? Already, the audience will feel as though they’ve gotten to know these characters. This works for longer dialogue, too: allow the character’s personal beliefs, life philosophy, and generally disposition to dictate how they talk, and your readers will thank you. Of course, this example is also good for giving the reader a general sense of what the characters’ relationship is like. Which brings me to my next point: 2. Allow the dialogue to show the character’s relationship. Everyone is a slightly different person depending on who they’re around. Dynamic is an important thing to master, and when you nail it between two characters, sparks can fly. Work out which character assumes more of the Straight Man role, and which is quicker to go for lowbrow humor. Think of who’s the more analytical of the two and who’s the more impulse driven. Who would be the “bad cop” if the situation called for it. Then, allow for this to show in your dialogue, and it will immediately become infinitely more entertaining. Example: “Alright,” said Fogg, examining the map before him. “Thus far, we’ve worked out how we’re going to get in through the ventilation system, and meet up in the office above the volt. Then, we’re cleared to start drilling.” Passepartout grinned. “That’s what she said.” “Oh, for the love of God – REALLY, Jean. Really!? We are PLANNING a goddamn bank robbery!” Some more questions about dynamic to ask yourself before writing dialogue:

3. Think about what this dialogue can tell the reader. It’s better to fill the reader in more gradually than to waist your valuable first chapter on needless exposition, and dialogue is a great way to do it. Think about what your characters are saying, and think about ways in which you can “sneak in” details about their past, their families, and where they came from into the discussion. For example, you could say: Tuckerfield was a happy-go-lucky Southern guy with domineering parents, and bore everyone to death. Or you could have him say: “Sheesh. All this sneakin’ around in the woods late at night reminds me of being back in Kansas. Good times, man, good times.” There was a pause, before he added, “‘Course, it wasn’t nearly so fun when I came home late for curfew and had to sleep on the front step, but y’know. Life happens.” Isn’t that much better than the omnipresent monotone? Dialogue is also a great way to fill in potential plot holes early on, by having your characters talk them out and explain them. Moreover, dialogue can also be used to foreshadow, offer relevant hints about the climax, or provide information necessary for the resolution. So use it wisely! 4. Sprinkle in mini-actions throughout. Even in actionless dialogue, no one actually does nothing. In my case, for example, I stim a lot. I play with my hair. I play with eating utensils. It’s probably very annoying for those around me, but you get the point. Less fidget-y folks might not do this as much, but they rarely sit totally still during conversations, either. So occasionally add in these mini-actions, and it will make your characters feel a bit less like disembodied voices or floating heads. For instance: Jo leaned back in her chair rolling her stiff neck from sitting still for so long. “…So the way I see it,” she continued. “Even if Pheris Beuller’s Day Off didn’t take place in Cameron’s imagination, Pheris was clearly a sociopath whose behavior shouldn’t be glamorized.” “Ha. As if.” Avery paused to sip her root beer. “Pheris,” she began, raising an index finger. “Was clearly emblematic of counterculturist movements such as the Beat Generation, and his disregard for the capitalistic dogmas imposed upon younger generations is something to be admired.” “For Christ’s sake, will you two lighten up?” scoffed Leo, counting out bills for the pizza. “We were talking about which movie we wanted to watch tonight. Jesus.” 5. Remember how people actually speak. In real life conversations, people don’t speak in paragraphs. Alright, some people might, and this can actually be interesting as the personality aspect of a certain type of character. But generally speaking, people don’t speak in paragraphs, or as though they’re writing thought-out prose or letters. In real conversations, people stutter. They laugh at their own jokes, repeat words or phrases, and lose their train of thought. Naturally, you don’t have to illustrate in your writing exactly how chaotic and mundane human speech can be, as writing would be pretty boring in general if it was strictly limited to miming reality. But it’s good to keep in mind that your characters are talking, not writing in purple prose. Exhibit A: “When I was a young boy, my mother and I had a most tumultuous relationship,” said Marcus. “She saw me as a hallmark of her past failures, and took every opportunity to remind me as such.” Exhibit B: “My mom, when I was kid, we had what you’d call a sort oftumultuous relationship,” said Marcus. “Nothing I ever did was right for her. She, uh – I think she saw me as sort of a hallmark of her past failures. Took every opportunity to remind me of that.” Which of these is more organic, more easy to visualize, and more telling of character? Unless the point of this dialogue is to illustrate that Marcus is a gentleman crook of some kind with pristine speaking mannerisms, I’m going to say the latter. Best of luck, and happy writing! <3

1 Comment

Leave a Reply. |

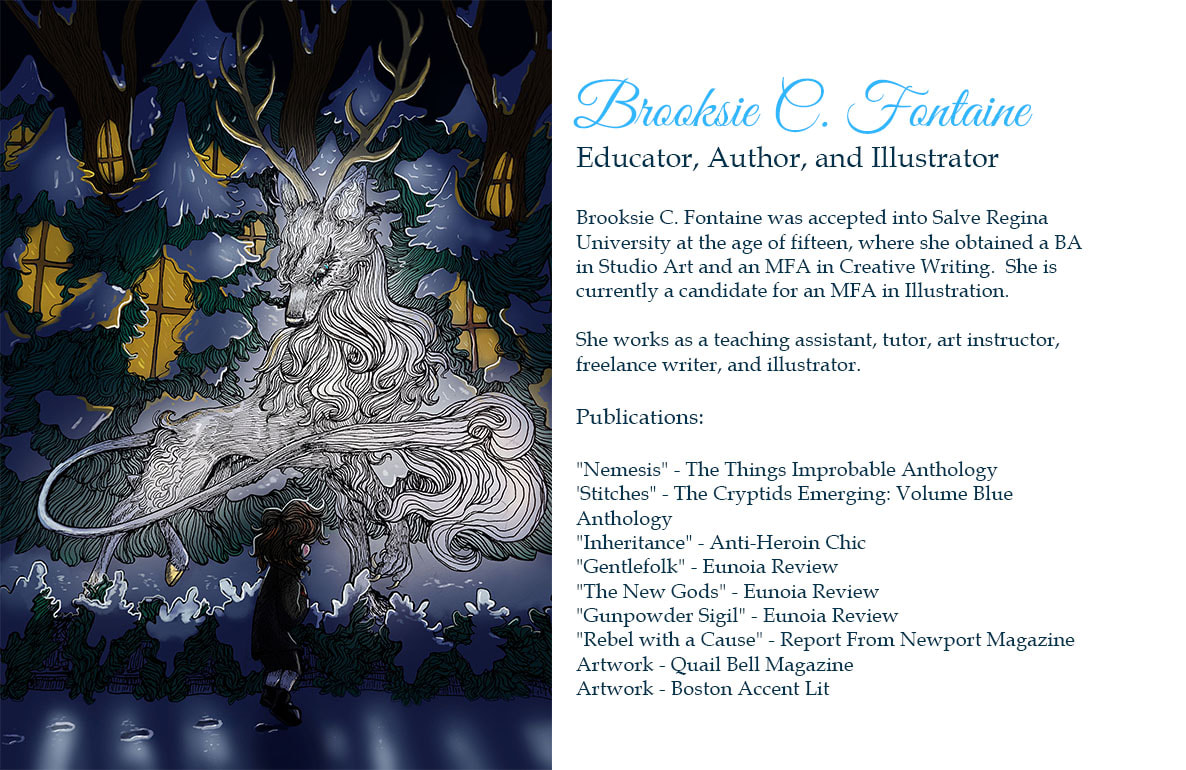

About the AuthorBrooksie C. Fontaine was accepted into college at fifteen and graduate school at nineteen. She has an MFA in English, and is currently completing a second MFA in Illustration. Archives

March 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed