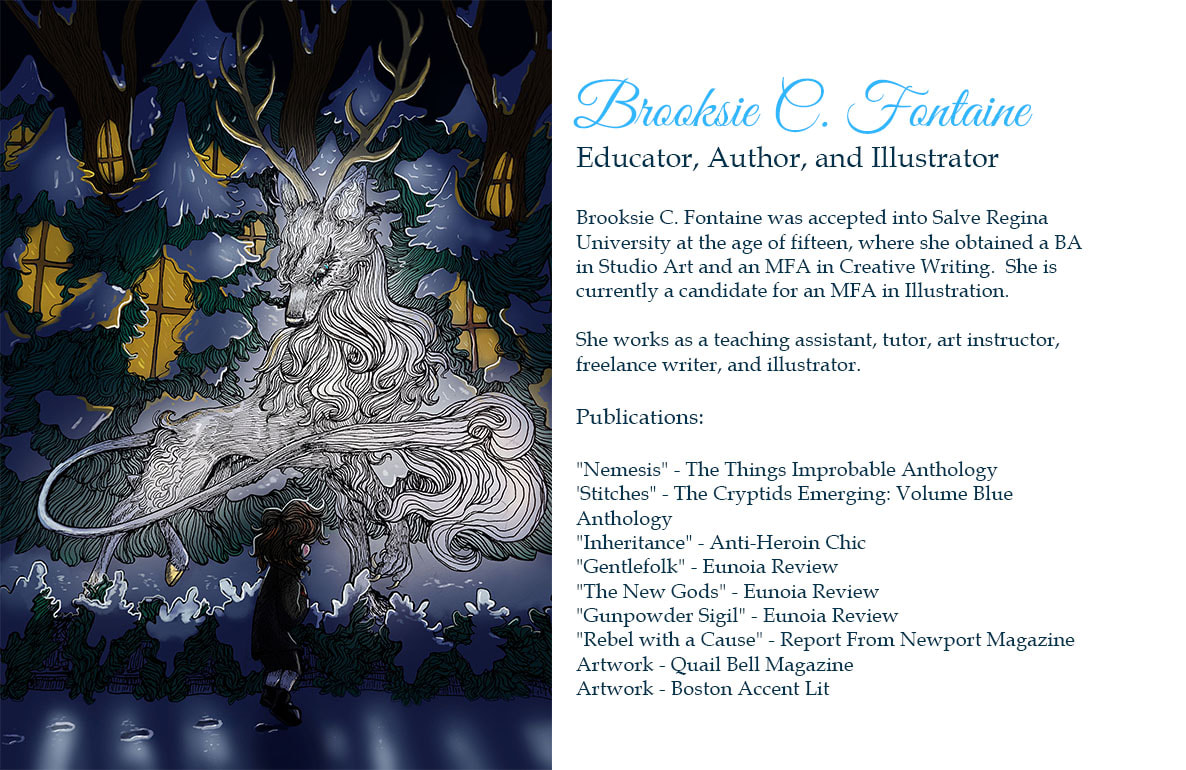

|

Fiction

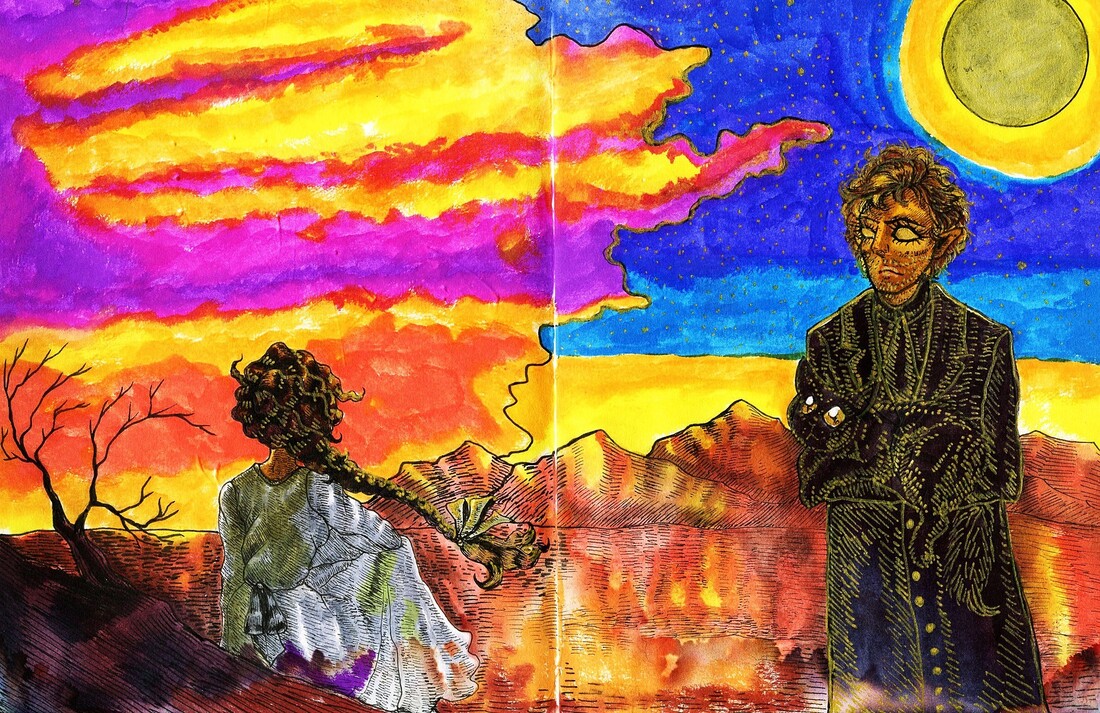

"Nemesis" - The Things Improbable Anthology A lovesick supervillain is confronted by what they will do for their beloved superhero. Publishing February 28, 2023. 'Stitches" - The Cryptids Emerging: Volume Blue Anthology A son escapes from his father's legacy. Published December 28, 2021. "Inheritance" - Anti-Heroin Chic Expecting parents build their secrets into their new house. Published September 22, 2020. "Gentlefolk" - Eunoia Review A timid woman faces her deepest fears in order to try and reclaim her stolen child from charismatic local Nature Gods. Only to discover that everything she’s been taught about them might be wrong. Published August 20, 2020. "The New Gods" - Eunoia Review Society is populated by gods, new and old. Some are more frightening than others. Published February 11, 2020. "Gunpowder Sigil" - Eunoia Review In a windblown Western town, a young girl conducts a summoning ritual for a spectral gunslinger. Magical realism meets the Western. Published August 4, 2019. Non-Fiction "Rebel with a Cause" - Report From Newport Magazine My experience choosing to pursue a career in Writing and Illustration, and to continue my student career with the Newport MFA in Creative Writing. Illustration Artwork - Quail Bell Magazine Fantasy illustrations from my "Heavenly Creatures" series, as well as for my story, "Gentlefolk." Published July 21, 2021. Artwork - Boston Accent Lit Illustrations from my "Heavenly Creatures" series, featuring gods, angels, and otherworldly creatures. Published December 31, 2018.

0 Comments

By late August, Summer has developed deep, beautiful lines on her golden face, and she’s got a red-haired baby on her hip. “Autumn,” she explains.

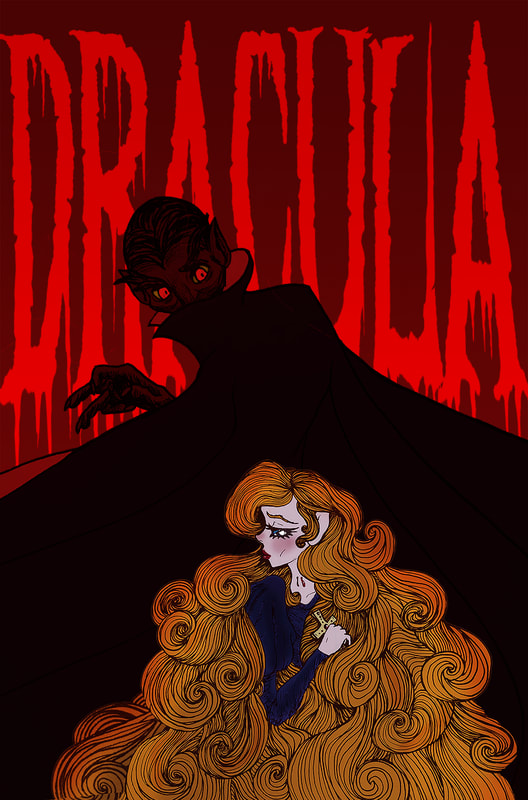

This is the way of seasons. Each year, they’re reborn anew. Summer was born to aging Spring, blossoms falling from her lavender grey hair. Spring, to the cold but caring hands of Winter. They help each other until they can stand on their own. “I wish I could know you when you’re young,” says Autumn. By September, he can speak for himself, and his curls have grown dense. Pumpkin-colored freckles have blossomed beneath his apple cheeks. “I wish I could know you when you’re old,” smiles Summer, sleepily. It’s nearly time for her to begin her hibernation. “Say hello to Winter for me, won’t you? Care for him kindly when he’s born. I never get to see him.” “Are you leaving already, Mother?” Autumn never feels ready. But just in the course of this conversation, he’s grown. His voice has deepened like rich coffee, warm in the suddenly chilly morning. “Soon. Never forever. I’ll see you next year.” Dracula and Mina, by Brooksie C. Fontaine (me!) IntroductionMore than a century after its publication, Dracula remains an intoxicating read. Adaptations (with some exceptions) seldom capture the sense of dread the titular vampire invokes, let alone how or why. Similarly, it’s seldom acknowledged or appreciated how hopeful and warm the novel eventually becomes. Even typing it outright that Dracula is, indeed, a hopeful and warm novel feels absurd. And yet, to me, the book practically overflows with love – even love towards Dracula himself, and I’ll elaborate on how and why later. In order to explain what I mean by this, I will break my analysis into sections. To understand the salvation of Dracula, one must first understand the true source of its terror. Thus, the first section of this analysis will be dedicated to the terror of the novel, and what the antagonist represents. The second section will be dedicated to the antithesis of Dracula’s terror – that is, the love the characters develop for one another, and their faith that goodness will prevail. The Horror of DraculaBefitting a book bearing his name, Dracula assumes the spotlight for the first portion of the novel – as does everything he represents. Through the diary entries of poor Jonathan Harker – a solicitor who just wants to do his job, only to be held hostage by sadistic vampires – we experience what it’s like to be a prisoner in Dracula’s castle. For a modern reader, this initially almost comes across as rather comical: a solicitor, dedicated to doing his job even while trapped in an inhospitable and gothic domain, negotiating with a client who regularly exits the building by scaling down it “in lizard fashion.” Someone get this man a raise. Jonathan’s imprisonment, however, quickly becomes a claustrophobic, carnivorous nightmare. Dracula casually feeds a baby to his three brides, and has the mother devoured by wolves (he has a command over most carnivores). As for Dracula himself, as he is described in this original text, he is far from the dashing prince of darkness that other adaptations sometimes depict him as: there is nothing appealing about the mental visual of Dracula, flesh slightly bloated from his feast, eyes open and unseeing as he “sleeps” in an earth-filled coffin. This place – Dracula’s castle, which is really an extension of Dracula’s character – is devoid of love, warmth, and safety. Jonathan's only protection is the crucifix around his neck, gifted to him by worried locals as he traveled to Dracula’s castle. And what little solace he has comes from the thought of his betrothed, Mina, and the hope that they may be reunited. We don’t get to enjoy much of that comfort, however; for most of the first portion of the book, we really have no way of knowing if Jonathan will be alright (unless we skip ahead or read the Wikipedia summary) and we’re deprived of any other comforting or benevolent presence. As we discover later, the protagonists – Jonathan, Van Helsing, Mina, Lucy, Dr. Seward, Arthur, and Quincey – represent persevering love, warmth, affection, and faith. Dracula is the absence of that. Perhaps this, then, is the horror of Dracula: a loveless existence, driven only by the need for consumption – and, as represented by the skin-deep beauty and provocative nature of the brides, other carnal impulses, such as sexual relief. Indeed, the trauma Dracula inflicts on Jonathan, Lucy, and Mina does feel evocative of sexual trauma, and his method of attack – which involves penetration via his teeth and the exchange of fluids, often in the victim's bedroom – feels evocative of sexual violence. Other real-world horrors Dracula evokes include the abuse of peasant and working-class populations by aristocracy – Dracula literally feeds on the impoverished populations of his country, taking their children, and they have little means of recourse against the tyrannical vampire. Moreover, the illness that overcomes his victims before their death and transformation is extremely evocative of tuberculosis, which plagued Victorian society. The horror of Dracula does not end there, however. Nor does it end with the terror of Dracula’s relentless consumption, demonstrated hauntingly when he feasts on the entire crew of the ship that was unfortunate enough to unknowingly carry his coffin among its cargo. The horror of Dracula comes from the concept that Dracula’s evil is infectious. Even Dracula himself was a great man whose body was possessed by a malevolent force, which was then spread to his brides – also innocent women, possessed by an evil that feeds upon children – and which he also temporarily spread to Lucy, before her reanimated body is killed out of mercy. During the final act of the novel, Mina’s potential transformation spurs a race against time to slay Dracula, lest she transform into a vampire herself. More on that in a minute. Before any of that, however, there’s already the sense that Jonathan – a prisoner in Dracula’s castle – must adopt some of his characteristics in order to figure out his predicament and survive. Like Dracula, he scales the castle wall, first to get into Dracula’s room and then, presumably, to escape. By necessity, he must entertain violent thoughts, and be willing to act on them – to allow Dracula to continue to exist would be an evil in and of itself. Unfortunately, Dracula’s hypnotic stare prevents Jonathan from following through, even when Dracula is “sleeping” with his eyes open. The fact that Dracula dons Jonathan’s clothes to prey on the locals contributes even more to this sense of convoluted and corrupted identity. This is a precursor to the true terror of Dracula, which grows more pernicious with each of his prospective victims. Lucy’s death and reanimation raises the stakes (no pun intended) for the rest of the novel. It was terrible enough to watch the sweet, bubbly Lucy be taken by illness, Van Helsing and co. working tirelessly to save her via transfusion after transfusion, but it’s even worse when it becomes clear what she’s become: a vampire who preys on children. When the same men who struggled to save her end up mercy-killing her reanimated body, it feels like a relief. Finally, the narrative is brought full-circle with Dracula’s attempt to transform Mina Harker, who serves as the emotional core of the novel. This compels the characters to pursue Dracula to the place where the story began – his castle – and repeats some of the themes that began with Jonathan’s imprisonment: in order to defeat Dracula, Mina must become a little bit like him. Partially transformed and edging more towards vampirism by the day, Mina is able to partially follow Dracula’s actions via this unique connection. This isn’t to make it sound as though Mina girl-bosses her way to Dracula’s castle without any difficulty. The scene in which Dracula forces Mina to consume his blood is grotesque, almost too evocative of real-life violence, and Mina’s descent towards vampirism is a tense affair. When attempting to receive a blessing, the holy water burns a cross into Mina’s forehead, and she breaks down at being rendered “unclean.” To top it all off, virtually all of the characters now have trauma surrounding Dracula and vampires. I haven’t mentioned this yet, but all the male main characters except for Van Helsing and Jonathan Harker have proposed marriage to Lucy (she graciously rejected Quincey Morris and Dr. John Seward, but accepted Arthur) and all continued to dearly love her as a friend, making her death and reanimation all the more horrific. Their final confrontation with Dracula is relatively brief, but the tension leading up to it is palpable. How, then, is Dracula defeated? More importantly, how is he defeated without the main characters becoming like him? The Salvation of Dracula I’ve already covered that OG Dracula is a brutal, nasty, and frankly terrifying character. There’s no mercy or empathy to get in the way of his appetite, his shapeshifting abilities create the sense that he could be anywhere and everywhere. Unlike his reincarnations of Sesame Street or Hotel Transylvania, there is the sense that he is inherently evil and connected to Satan. Dracula is acutely aware, however, that if such evil exists, then good must be at least as powerful. And the forces of good are just as present throughout the novel as Dracula himself, taking the form of the love the characters have for one another, their cleverness and resilience, and the faith they increasingly rely on for strength and comfort. This book is often brutal, but it is never cynical; it is earnest in its belief in good over evil, and importantly, that belief never detracts from the terror that evil evokes. I’ve focused mostly on Dracula’s character thus far, so let’s talk a bit about our protagonists; in my opinion, they’re equally as important. The first we get to know is Jonathan “Get This Man A Raise” Harker, who was not only held hostage by a vampire, but escaped with his life. He is, understandably, traumatized by the encounter, arriving delirious in a Budapest hospital. Before his daring escape, the last word in his journal entry is Mina, his beloved fiancée (and shortly afterwards, wife). Wilhelmina “Mina” Harker, nee Murray, is arguably the emotional center of the novel, a character whose faith, inner strength, mercy, and perseverance helps all of the other protagonists survive. She represents all the positive traits that the undead lose. A quiet and introverted young schoolmistress, she is entirely faithful to Jonathan, and he immediately trusts her with his journal entries chronicling the terrors of Dracula’s castle. After this exchange of insurmountable trust, they’re married in the hospital. Mina’s best friend, Lucy Westenra, is a little (a lot) more outgoing. Bubbly, sweet-natured, and self-confident, she writes (impressively, without sounding like she’s bragging about it) about receiving three marriage proposals in one day. She says she’d like to marry all of them, but can only accept one – that of the wealthy young heir Arthur Holmwood, who also becomes an important character in the remainder of the novel. Lucy’s other two suitors, the adventurous American Quincey Morris, and the psychiatrist John Seward, handle the rejection beautifully. It’s no exaggeration that they could give lessons to today’s young men, and they immediately reassure Lucy. As a result, all of them remain friends. Finally, we have Professor Abraham Van Helsing, one of my favorite characters. Though Mina represents the emotional strength needed to defeat Dracula, Van Helsing represents the knowledge and cleverness (though Mina has plenty of moments of cleverness, and Van Helsing can be pretty darn emotional, becoming overwhelmed at Lucy’s funeral). He is the first one to identify that Dracula is a “nosferatu,” and that he is preying on Lucy. It is Lucy that brings these characters together – first, Mina (and by proxy, Jonathan) through her friendship, then Arthur, Dr. Seward, and Quincey via their proposals, and then Van Helsing and through her vampiric illness. It is through her illness that we see a demonstration of the love these men have for her – each gives a transfusion of blood which briefly restores her, only for it to be drained by Dracula during his nocturnal visits. Even Van Helsing donates a vast quantity of his own blood, as he comes to serve as a father figure – both to her and to Arthur, who resembles Van Helsing’s own deceased son. Throughout the book, it’s increasingly clear that he’s a paternal presence to the other characters as well. The final act of the novel is set into motion when Mina is forced to drink Dracula’s blood, and it becomes a race against time to kill him before she transforms into his undead bride. But what I find even more noteworthy is the manner in which the characters rally around Mina emotionally, and the manner in which Mina, in turn, gathers every ounce of emotional fortitude she has to be strong and cheerful. To me, it is the manner in which the characters love and support one another that makes the novel so compelling. In another novel, Quincey, Doctor Seward, and Arthur might have a bitter rivalry for Lucy’s affection, but they come to love one another as brothers. Mina becomes friends with all of the male characters, comforting them and receiving comfort in turn, and Jonathan never shows even a flash of jealousy. In the face of adversity, they become family. This makes it all the more devastating when Quincey is killed – living just long enough to see Dracula defeated and Mina’s curse lifted – and all the more meaningful when Mina and Jonathan name their child after him. One of the final images in the book takes place in the epilogue, seven years later, in which little Quincey is sitting on Van Helsing’s lap as the group reflects on their shared experiences. It is an unequivocally happy ending, devoid of any implications that Dracula will return – something we may come to expect, after being steeped in the cynical, sequel-baiting modern horror genre. But as I said before, this is not a cynical book. Not only did the main characters earn their happy ending, but Dracula, too, found release – that is, the human Dracula, who was also condemned to walk the earth as a member of the undead. One of the most touching yet overlooked aspects of the text is the moment when Dracula is impaled, and his expression before crumbling to dust is one of relief. It is at times a brutal book, but not a cruel one, and demonstrates how even one of the most famous antagonists of all time is, himself, a victim of the forces of evil. Conclusion What can writers of today learn from Dracula? A lot, it turns out.

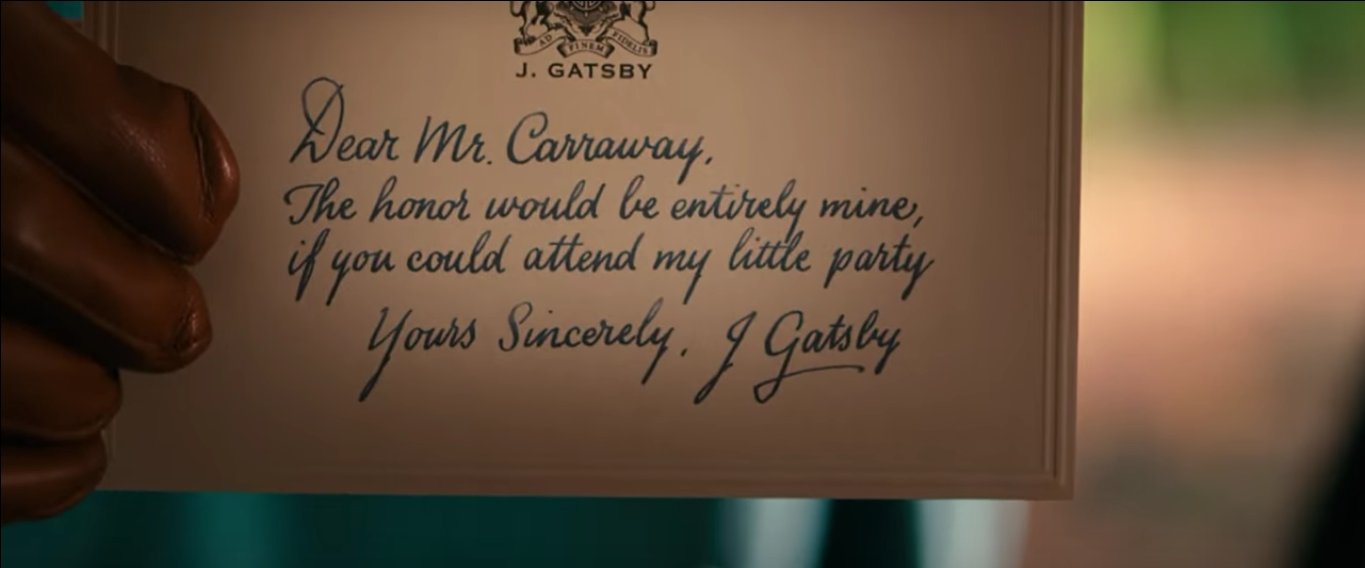

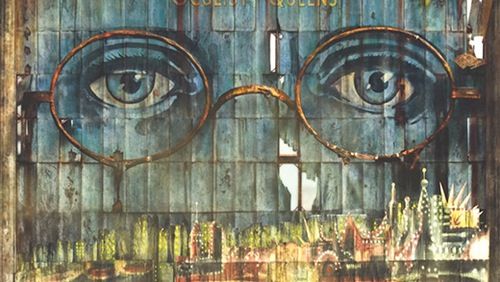

From the many distinctive voices of the characters that intertwine to form the narrative, to the layers of dread woven into the narrative (the surface-level horror of a ghost ship arriving with a murdered crew, and the symbolic horror of lost identity), many of the novel’s lessons have proven ageless. To me, Dracula is also a study in how to make your audience care about your characters, by making your characters earnestly and wholeheartedly love each other. All were brought higher by the adventure they undertook together, arriving in a spiritually better place by the end of the book than they were when they began. The distinguished yet lonely and brokenhearted Van Helsing finds a new family, the bookish and introverted Mina proves courageous in the face of a vampire, and Jonathan, a man of insurmountable dedication, now more than ever deserves a raise. Dracula is one of the greatest horror novels of all time, but it is also an unabashed study of the redemptive and enduring power of love, and proof that soulmates are sometimes the family you build for yourself. Introduction In my younger and more vulnerable years, my father gave me some advice that I’ve been turning over in my mind ever since. “Whenever you feel like criticizing any one,” he told me, “just remember that all the people in this world haven’t had the advantages that you’ve had.” So opens one of my all-time favorite works of literature, a richly written book with prose that’s bright and dark and begs to be consumed in gulps. It is, in many ways, a tone-setter for the pages to come: the book is often a rumination on various degrees of advantage – or rather, on class, wealth, and the distinction between the two. On Old Money, and the suspicion with which Old Money regards New Money – despite the fact that all Old Money was once New Money, and initially amassed itself through similarly unscrupulous means. Only time provides it with the illusion of cleanliness. The book is also preoccupied with appearances, and the manner in which we cast the spotlight of judgment on others. All of this is alluded to in the first few words of the book. It is also a somewhat humorous opening line, in the context that its narrator, Nick Carraway, spends the rest of the book criticizing and judging everyone around him. I can think of few literary burns so searing as, “one of those men who reach such an acute limited excellence at twenty-one that everything afterward savors of anticlimax.” “He peaked in college” simply does not have the same ring to it. Nick is a judgmental person, and it’s through his judgements that we form our own assessments of the world around him. This, in and of itself, is not a criticism of Nick. Though he’s far from perfect, I like Nick – he feels like my guide through a titanic world of larger-than-life figures that would otherwise be overwhelming, as Virgil was to Dante. For this reason, despite his own flaws, Nick has been the recipient of a fair degree of affection from readers. If anything, his subtly scathing view of the other characters only stokes our sense of camaraderie towards Nick. The Great Gatsby is a book full of absurd rich people making poorly thought-out, careless choices, and the narrative is somewhat contingent on the fact that we’re aware of that. Just as it’s contingent on humanizing them to a degree, and alluding to inner complexities of their own that even Nick’s wry observations can’t perceive. I tinkered with a few prospective titles for this piece. The Great Gatsby: A Failed American Dream, The Great Gatsby: Dehumanization Through Symbolism, and The Great Gatsby: An Ode to the Fleeting Past, were a few that came to mind. The Great Gatsby: Literature’s Best Drunk Driving PSA was a briefly considered fourth option. But ultimately, Gatsby is too thematically multifaceted to reduce my interpretation of it to a single theme. So I’ll break them down, one by one, and how they form the foundation on which the novel is built. A Failed American DreamDefined by the Oxford English Dictionary as “the ideal that every citizen of the United States should have an equal opportunity to achieve success and prosperity through hard work, determination, and initiative,” the American Dream is as ripe for rumination as it is for pursuit. The American Dream is ultimately that of a meritocracy, in which anyone, regardless of background, can achieve their goals and socially ascend if they’re hard-working and qualified. Importantly, the thesis of The Great Gatsby has nothing to do with whether or not the American Dream is possible to achieve for anyone, and instead focuses on the specific manner in which its central characters fail to achieve it – and demonstrates that though we may have won independence from the British, we’ve never quite shaken the ideals of the aristocracy. Gatsby bears the title of the book for a reason, and it has very little to do with Gatsby’s most authentic traits as a person. If it were truly about Gatsby the man, it wouldn’t even be called Gatsby, but Gatz – referring to James Gatz, Gatsby’s real name. Though I have no proof for this, I do maintain that the stolen name of Mad Men’s Don Draper – who, in many ways, embodied the American Dream as it was incarnated throughout the 1960s – was inspired by Gatsby’s spur-of-the-moment decision to change his name. Though unlike Draper, who stole his fallen comrade’s name to escape gruesome combat conditions, Gatsby changed his name only to fit the lofty ideals he held for himself and the drudgery of his social class. The truth was that Jay Gatsby of West Egg, Long Island, sprang from his platonic imagination of himself. He was a son of God (...) and he must be about His Father’s business, a service of vast, vulgar, and meretricious beauty. In terms of his mortal mother and father, Gatsby was begotten by “farm people” whom “his imagination had never really accepted” as his parents. He was frustrated by them, by his attempts to attend college (which required working as a janitor – work he viewed as beneath his grand ideals), and by his early encounters with women, towards whom he was “contemptuous (...) of young virgins because they were ignorant, and the others because they were hysterical about things which in his overwhelming self-absorption he took for granted.” It is an interesting contrast to his later obsession with Daisy, though as I’ll elucidate later, I doubt his self-absorption ever truly waned; rather, Daisy became a part of his grand vision for himself. Progressing further into the novel, I’m inclined to believe this has to do with class, because he had no such qualms with Daisy – the first “nice” (or rather, rich) girl to let him into her life, and he appears just as enamored by her house and her lifestyle as he is by her. Gatsby, to an extent, appears to be aware of this. When Nick speculates on what it is that makes Daisy’s voice so magical, Gatsby replies, seemingly to his own surprise, that the magic in her voice was “money.” The problems with heaping such vast amounts of personal symbolism on a human being will be discussed shortly. Suffice it to say, Gatsby may have had lofty aspirations since childhood, but Daisy became the pillar around which he built them. The entire persona of Jay Gatsby became dedicated to what he perceived Daisy to be: after buying a mansion across from hers, he threw wild parties in the hopes of enticing her, and then stopped them just as abruptly when he decided she didn’t like them. Nick describes Gatsby’s persona, though charismatic to pull it off, as a borderline parody of aristocratic mannerisms. Gatsby made Daisy into a goddess, and his life into her temple. Before we get too far down the rabbithole of ascribing symbolism to human beings – I have an entire section dedicated to that – let’s return to Gatsby’s relationship with the American Dream. On a surface level, he is a tremendous success story: even if his wealth was the result of some affiliation with organized crime, the fact remains that Gatsby was the child of impoverished farmers who dreamed his way into a lavish mansion and a life of decadent parties, full of movie stars, politicians, gangsters, and financial moguls of every caliber. In his pink suit and gilded-yellow car and shining mansion, Gatsby seems to encapsulate the American ideal that anyone can become someone. For all his greatness, however, Gatsby failed to achieve true prosperity. His funeral was attended only by his father, by Nick, and by a nameless owl-eyed man whose round spectacles evoke the all-seeing gaze of T.J. Eckleburg (a.k.a. God – his other Father, as Nick alluded to with Gatsby’s “platonic conception of himself”). In other words, though Gatsby achieved riches and fame, he remained impoverished with regards to love, authenticity, and genuine connection. All the other main characters illustrate similarly flaccid fulfilments of the American Dream. Daisy and Tom Buchanan were born into the kind of life Gatsby wanted, and both had something that he could never earn: Old Money. Though wealth can be accumulated, the class difference remains impermeable – described in the book as a “sheet of barbed wire.” And yet, Daisy and Tom are miserable people. Daisy is fully aware her husband is cheating on her, and feels, on some level, deeply unsatisfied with her life. Within pages of her introduction, she sadly remarks that the best thing a woman can be is a “beautiful little fool.” She says this with regards to her daughter, whose birth Tom is implied to have missed while he was out having a tryst. As for Tom, he is deeply insecure, and makes it everyone else’s problem. He alludes, at various points, to being jealous of Gatsby, and even more explicitly is threatened by the very existence of people of color – he makes derogatory reference to The Rise of the Colored Empires within a few pages of his introduction, and later makes an equally perplexing reference to interracial marriage while disparaging Gatsby and Daisy’s affair (especially strange, since Gatsby and Daisy are both white, as Jordan Baker sheepishly points out). Tom was born into money and social privilege of every kind; he has nothing upon which to build his self-esteem other than the way he was born. And he clings to it, this notion of inherent superiority based only on his race and class – because he really doesn’t have anything else upon which to base his identity. Of course, because they were born into wealth, the Buchanans might be disqualified from pursuit of the American Dream to begin with, because they have very little to aspire towards. They were born at the top of the social food chain, and it’s no coincidence that both of their lower-class lovers have been killed by the end of the book while they, as Nick puts it, “retreat back into their wealth.” But even if they had done anything to earn their status, could they truly be considered prosperous? They’re practically bankrupt when it comes to maturity, self-worth, and true joy. Nick himself concludes his final interaction with Tom with the realization that he’s talking to a giant child, who’s never truly had to face consequences or overcome obstacles. Nick himself has a complicated relationship with the American Dream. He hasn’t given up on achieving prosperity, but he certainly has become disillusioned by the brand of prosperity represented by New York and its Old and New Money. In the short term, he has given up his attempts to achieve success as a New York bond salesman, and resolved to return West – from which he, Daisy, Tom, and Gatsby all originally hailed. I won’t be touching on Jordan Baker’s relationship with the American Dream, though not for lack of interest – only for lack of conclusive knowledge. Jordan is one of my favorite characters, and though we find out little about her inner life, we get the sense that she has a complex internal world beneath her aloof, feline exterior. Returning to the other characters, whom we get to know somewhat more conclusively, it could be that none of them were pursuing the right things, and had the wrong definition of prosperity. Money isn’t meaningless, but happiness seldom comes from assigning superiority exclusively to wealth, and defining betterment exclusively as the accumulation of it. The Great Gatsby is aware that there’s more to life than decadence and wealth. In one of the most subtly impressive elements of the book, Fitzgerald makes a billboard into a character, and curiously, one of my favorite characters; from the industrial area dubbed “the City of Ashes,” the spectacled blue eyes of T.J. Eckleburg are all seeing, and represent the eyes of God. A reminder that past the facade of luxury, there exists right, wrong, and truth. And beneath the layers of symbolism that envelop each character, there exists a flawed and multifaceted human soul. Dehumanization Through SymbolismThe Great Gatsby is full of symbolism. Almost everything represents something else. We all know T.J. Eckleburg is God, but the green light is also Daisy, and Daisy is the American Dream – at least, she’s the American Dream to Gatsby. By the end of the book Gatsby has become Nick’s green light – representing, to Nick, a dream so pure and unattainable that the world had to kill it. And of course, the green light is green for a reason – it represents money, the kind of inherited wealth that Gatsby so admires. Complicating things further, throughout much of the novel, Gatsby is his house, built recently but designed to look old, in the same way Gatsby’s extravagance tries to impersonate old money. This is all well and good as a reader, but it’s problematic to ascribe this much symbolism to people within your own life. Which is what the characters – especially Gatsby – are doing, all the time. In Gatsby’s case, he mythologizes human beings to the point of his own downfall. To be clear: there is something to admire about Gatsby, something appealing about a farm boy who dreamed his way out of the dust and dirt and into a glorious new life of explosive parties and extravagance of every kind. If that life feels like a dream, it’s because it is one – Gatsby’s dream, which he summoned up and walked into. We like wily, ambitious, class-hopping protagonists. Look how audiences reacted to Don Draper, whom I touched on earlier as a spiritual cousin to Gatsby, or Tommy Shelby of Peaky Blinders, who came from his own Valley of Ashes and whose spectacled blue eyes coincidentally look exactly like those of T.J. Eckleburg. We all know on some level that society wants to confine us, to homogenize us, and we root for people who are clever and perseverant enough to defy its boundaries. However, this vision is only admirable when applied to oneself. You can’t dream other people into what you want them to be, or make them into a dream that doesn’t reflect who they are. This is exactly what Gatsby does for Daisy, by making her into his symbolic green light and dedicating his worship to her without ever stopping to consider Daisy the human being. Daisy is no saint – she’s feeling insecure in her relationship, and by the end of the book, that’s somehow led to a body count of three people. My girl has problems of her own. But Gatsby’s love for Daisy is far from selfless. I refute the interpretation that Gatsby built his life and persona for Daisy – he already had grand ambitions for himself, since before he even christened himself Jay Gatsby as a teenager, and Daisy only became the living embodiment of them. I would argue that if he hadn’t chosen her as his object of worship, he would have found someone or something else to embody his dreams of wealth. Tom is an unfit husband in many ways – a serial adulterer, prone to “little sprees,” as he calls them. However, we never see any indication that Tom’s wayward nature is a primary motivation for Gatsby rekindling his relationship with Daisy, or that his greatest concern is making sure she’s happy. He never even appears to take into consideration the well-being of Daisy’s preschool-age daughter; when briefly confronted with the child, he seems baffled by her existence. Complicating things further, the little girl asks for her father – indicating that she does have some kind of a bond with Tom, as poor a role model as he may be. Neither Daisy nor Gatsby seem to consider her, even as collateral damage in their affair. Back to Gatsby’s relationship with Daisy, it struck me that when describing what made Gatsby fall in love with Daisy, much of what he described was her house and her lifestyle. Her wealth seems to be one of the few barriers between her and the annoyance with which he regarded his other feminine conquests. When they first met, he enjoyed how many men had been with her before – it “increased her value” in his eyes – but he seems disgusted by her relationship with Tom, and insistent that Daisy tell Tom that she never loved him. He doesn’t just want her love, he wants to be the only man she ever loved. For her to be an object of universal male desire, but to be the only man she’s ever desired in return. This insistence leads Daisy to push back against Gatsby and assert that she did (and does) love Tom. “Oh, you want too much!” she cried to Gatsby. “I love you now – isn’t that enough? I can’t help what’s past.” She began to sob helplessly. “I did love him once – but I loved you too.” Gatsby’s eyes opened and closed. “You loved me too?” he repeated. Though Daisy hasn’t always given Gatsby what he’s wanted, it’s one of the few times she’s verbally contradicted him. This realization, that Gatsby is not the sole recipient of Daisy’s love, is in my opinion equally as baffling to Gatsby as the realization that Daisy HAS feelings of her own. That those feelings are sometimes unpleasant to him, or contradict what he might want from her. Of course, to be fair to Gatsby, this realization is accompanied by the more understandably unpleasant sensation that Daisy isn’t actually going to leave Tom. Up until this point, the reader, Gatsby, and Nick could understandably view this as a love story, in which formerly star-crossed sweethearts have the chance to reconnect. But this conversation comes with a reversal of fortune, in which everyone in the room (along with the reader) seems to realize the truth: that Daisy and Tom aren’t going to split up, at least not on Gatsby’s account. Daisy isn’t entirely committed to being with Gatsby, and though she clearly does have genuine feelings for him, the whole thing starts to feel more like a revenge-fling against her cheating husband. Though, importantly, we have no way of knowing – Nick has long talks with Gatsby, but few with Daisy. At least, few conversations revealing enough to disclose her true feelings and motivations. We see her through Nick’s eyes, who sees her largely through Gatsby’s eyes, and never through her own. This doesn’t mean Daisy is exempt from her own crimes. She did kill a woman, a crime for which she didn’t take responsibility. This, in turn, cost Gatsby his life. George, Gatsby’s murderer, takes his only life shortly afterwards. As Nick points out, she and Tom can always take refuge in the fortress of their generational wealth and status – and they do, while three people die as direct and indirect results of their carelessness. This isn’t entirely Daisy’s fault though, or even Tom’s. Daisy’s infamous hit-and-run appears to have been an accident, and to our knowledge, Tom never finds out that his wife was the killer and not Gatsby. The novel is similarly aware that Daisy could never have lived up to Gatsby’s expectations for her – from the moment they reconnected, she was doomed to fail him. He was culpable in his own downfall, simply by placing another human being on such a gilded pedestal. Gatsby isn’t the only character who mythologizes people. Nick mythologizes Gatsby – the book itself, which is implied to be written by Nick in-universe, is called The Great Gatsby, for a reason, and not The Okay Gatsby, or This Guy I Knew A Couple Years Ago, or Rich People Wilding Out. We’re mythologizers by nature; we mythologize people, places, and things, and The Great Gatsby serves as both a celebration of this tendency and as a cautionary tale. At its core, The Great Gatsby is a nesting doll of mythologization. Nick mythologizes Gatsby who mythologizes Daisy, but who really most of all mythologizes money, and even more than that, mythologizes the past and longs more than anything to repeat it and do it right this time. An Ode to the Fleeting PastYou don’t start writing about an experience until it’s already over – or at least, in the rearview window. The book itself is set in 1922 but was published in 1925 – by the time it hit the shelves, the earliest years of the Roaring Twenties were already past. Even in the context of the story, the characters reflect on the fact that their most carefree years are behind them – Nick has a moment of panic at the realization that he’s turned thirty, and Daisy, in the same scene, contemplates that if they were truly young, they’d have started dancing to the jazz music playing from the room below. To be clear, these characters are young. Thirty is young. And I’m not saying that to console myself – as I write this, I’m only twenty-four. And even I can see that thirty is young. But what thirty is not, is a child. It is not a teenager, or those years in your twenties where it’s still somewhat acceptable to act like one. All of these characters, especially the married ones, have responsibilities. Daisy and Tom even have a child, as scary as that may be. They can no longer act like they did five years ago, when Daisy and Gatsby were first in love, and with each passing year, that relatively carefree existence must look like more of a shining memory. Almost everyone idealizes the past to a certain extent. A summer we’re nostalgic for, a look we wish would come back into fashion, a chance to do it all over, a desire to shrink back into childhood and have your mother handle your bills and bring you cookies and milk. More broadly, we as a culture worship at the altar of youth. Twenty-four-year-olds playing seventeen-year-olds sell us an idealized, airbrushed version of teenhood. Countless films, books, and television shows have become vehicles of nostalgia for decades past. And just about everyone has people who are no longer in their lives whom they’d love to talk with again. Ironically, this yearning appears timeless. Gatsby’s greatest hubris was not in accumulating his wealth. It was not in his attempts to breach “the barbed wire” that separates social class, but in his determination to recreate the past. He boldly states as much: “I wouldn’t ask too much of her,” I ventured. “You can’t repeat the past.” “Can’t repeat the past?” he cried incredulously. “Why of course you can!” He looked around him wildly, as if the past were lurking here in the shadow of the house, just out of reach of his hand. “I’m going to fix everything, just the way it was before,” he said, nodding determinedly. “She’ll see.” Gatsby, in many ways, never matured. Nick himself reflects that Gatsby “invented just the sort (of persona) a seventeen-year-old boy would be likely to invent, and to this conception he was faithful to the end.” His inability to confront reality, to keep his feet on the ground while still reaching for the clouds, and to evolve past the vision of his teenage self – all this led to his downfall, drowning in the dreams that had buoyed him for so long. He couldn’t look at himself for who he was, couldn’t reconcile his past with his goals for the future; he couldn’t see Daisy’s flaws and continue to love her anyway; he certainly couldn’t accept that she had moved on with her life and continued on with his own. He had to have everything. As Daisy put it, he wanted too much. She yearned for the past in a similar way that Gatsby did, in her own way attempting to recreate what had come before. Tom, of course, is also terrified of a prospective future in which his race and class no longer make him automatically superior to others. Aside from his panic at turning thirty, Nick also wishes to return to the past, so he could defend Gatsby more or pay him more than the one compliment he offered him. All of the characters wish, on some level, to reclaim what was, and take shelter from the frightening unknown of the future. The Great Gatsby concludes with one of the most beautiful closing lines of all time. Its final page is full of yearning, not just for a few years ago, but for the continent as it was, when it was still untouched by settlers, when man came “face to face for the last time in history with something commensurate to his capacity for wonder.” An entirely different kind of American Dream. Gatsby believed in the green light, the orgastic future that year-by-year recedes before us. It eluded us then, but that’s no matter–to-morrow, we will run faster, stretch out our arms farther….And one fine morning – So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past. The words seem to groan under their desire to start over, to do it right this time, to cup the past and drink it. But all the while, the present is alive, ignored in favor of an idealized history, shining but untouchable behind us. ConclusionThe Great Gatsby is, perhaps more than any of this, a love story. Not between Daisy and Gatsby – or rather, not just between Daisy and Gatsby, as flawed and destructive as their relationship became – but between Gatsby and Nick.

When all the “shining hundreds” who attended Gatsby’s parties have vanished, along with Daisy back into her wealth, Nick is left behind to mourn Gatsby alone. He is still mourning him two years later, enough to write a novel-length manuscript to set the record straight and/or to make sense of what happened. In a book full of superficiality and betrayal, Nick’s feelings towards Gatsby – though not always without suspicion or annoyance or cynicism – were a current of genuine admiration that carried the reader along. By the end, it’s Nick looking out at the green light, to which he has ascribed Gatsby’s dreams. I have personal reasons to meditate on The Great Gatsby’s commentary on the past. I have my late grandfather’s copy – he gifted it to me when he was still alive, and I was too young to fully appreciate it. It was a gift I only fully received years after his passing, when I truly fell in love with it. His notes are still in the margins, and I jot down my own. His in red ink, mine in gold, the past and the present existing side by side. We can’t return to the past, but it will always exist within us, informing who we are, the earth from which our future will grow. And as the enduring beauty of The Great Gatsby proves, some things are timeless. One of my resolutions for 2020 was to write a very short story for each day of the year! This, I accomplished with the help of Twitter's writing community, and prompts such as #vss365 and #BraveWrite.

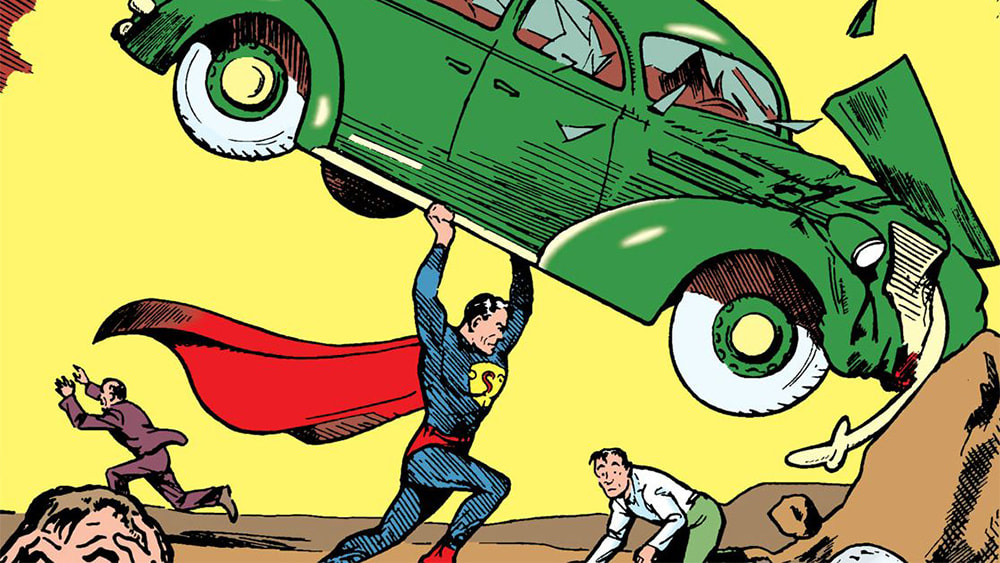

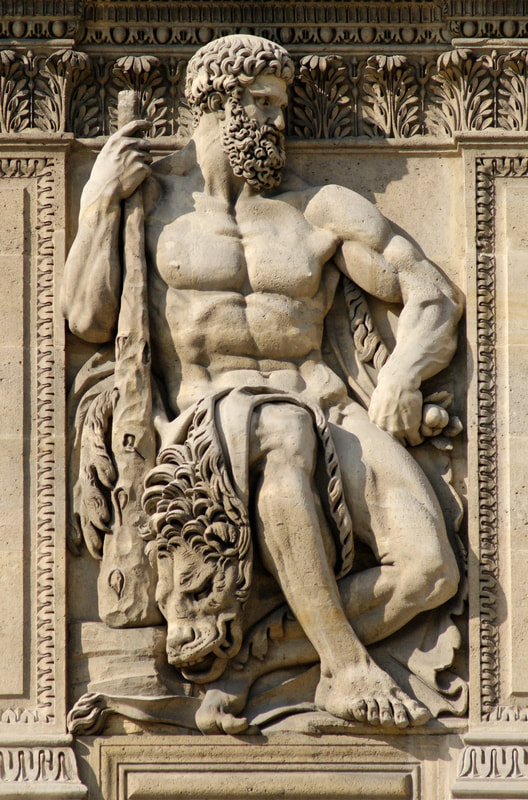

Below is the compilation of my efforts, including the original prompts and hashtags. By Brooksie C. Fontaine & Sara R. McKearneyFew tropes are as ubiquitous as that of the hero. He takes the form of Superman, ethically and non-lethally thwarting Lex Luthor. Of Luke Skywalker, gazing wistfully at twin suns and waiting for his adventure to begin. In pre-Eastwood era films, a white Stetson made the law-abiding hero easily distinguishable from his black-hatted antagonists. He is Harry Potter, Jon Snow, T’Challa, Simba. He is of many incarnations, he is virtually inescapable, and he serves a necessary function: he reminds us of what we can achieve, and that regardless of circumstance, we can choose to be good. We need our heroes, and always will. But equally vital to the life-blood of any culture is his more nebulous and difficult to define counterpart: the antihero. Whereas the hero is defined, more or less, by his morality and exceptionalism, the antihero doesn’t cleanly meet these criteria. Where the hero tends to be confident and self-assured, the antihero may have justifiable insecurities. While the hero has faith in the goodness of humanity, the antihero knows from experience how vile humans can be. While the hero typically respects and adheres to authority figures and social norms, the antihero may rail against them for any number of reasons. While the hero always embraces good and rejects evil, the antihero may embrace either. And though the hero might always be buff, physically capable, and mentally astute, the antihero may be average or below. The antihero scoffs at the obligation to be perfect, and our culture's demand for martyrdom. And somehow, he is at least as timeless and enduring as his sparklingly heroic peers. Which begs the question: where did the antihero come from, and why do we need him? The Birth of the Antihero:It is worth noting that many of the oldest and most enduring heroes would now be considered antiheroes. The Greek Heracles was driven to madness, murdered his family, and upon recovering had to complete a series of tasks to atone for his actions. Theseus, son of Poseidon and slayer of the Minotaur, straight-up abandoned the woman who helped him do it. And we all know what happened to Oedipus, whose life was so messed up he got a complex named after him. And this isn’t just limited to Ancient Greece: before he became a god, the Mesoamerican Quetzalcoatl committed suicide after drunkenly sleeping with his sister. The Mesopotamian Gilgamesh – arguably the first hero in literature – began his journey as a slovenly, hedonistic tyrant. Shakespearian heroes were denoted with an equal number of gifts and flaws – the cunning but paranoid Hamlet, the honorable but gullible Othello, the humble but power-hungry MacBeth – which were just as likely to lead to their downfall as to their apotheosis. There’s probably a definitive cause for our current definition of hero as someone who’s squeaky clean: censorship. With the birth of television and film as we know it, it was, for a time, illegal to depict criminals as protagonists, and law enforcement as antagonists. The perceived morality of mainstream cinema was also strictly monitored, limiting what could be portrayed. Bonnie and Clyde, The Good the Bad and the Ugly, Scarface, The Godfather, Goodfellas, and countless other cinematic staples prove that such policies did not endure, but these censorship laws divorced us, culturally, from the moral complexity of our most resonant heroes. Perhaps because of the nature of the medium, literature arguably has never been as infatuated with moral purity as its early cinematic and T.V. counterparts. From the Byronic male love interests of the Bronte sisters, to “Doctor” Frankenstein (that little college dropout never got a PhD), to Dorian Grey, to Anna Karenina, to Scarlett O’Hara, to Holden Caulfield, literature seems to thrive on morally and emotionally complex individuals and situations. Superman punching a villain and saving Lois Lane is compelling television, but doesn’t make for a particularly thought-provoking read. It is also worth noting, however, that what we now consider to be universal moral standards were once met with controversy: Superman’s story and real name – Kal El – are distinctly Jewish, in which his doomed parents were forced to send him to an uncertain future in a foreign culture. Captain America punching Nazis now seems like a no-brainer, but at the time it was not a popular opinion, and earned his Jewish creators a great deal of controversy. So in a manner of speaking, some of the most morally upstanding heroes are also antiheroes, in that they defied society’s rules. This brings us to our concluding point: that anti-heroes can be morally good. The complex and sometimes tragic heroes of old, and today’s antiheroes, are not necessarily immoral, but must often make difficult choices, compromises, and sacrifices. They are flawed, fallible, and can sometimes lead to their own downfall. But sometimes, they triumph, and we can cheer them for it. This is what makes their stories so powerful, so relatable, and so necessary to the fabric of our culture. So without further ado, let’s have a look at some of pop-culture’s most interesting antiheroes, and what makes them so damn compelling. Note: For the purposes of this essay, we will only be looking at male antiheroes. Because the hero’s journey is traditionally so male-oriented, different standards of subversiveness, morality, and heroism apply to female protagonists, and the antiheroine deserves an article all her own. Antiheroes show the effects of systematic inequalities.As demonstrated by: Tommy Shelby from Peaky Blinders. Why he could be a hero: He’s incredibly charismatic, intelligent, and courageous. He deeply cares for his loved ones, has a strict code of honor, reacts violently to the mistreatment of innocents, and demonstrates surprisingly high levels of empathy. Why he’s an antihero: He also happens to be a ruthless, incredibly violent crime lord who regularly slashes out his enemies’ eyes. What he can teach us: From the moment Tommy Shelby makes his entrance, it becomes apparent that Peaky Blinders will not unfold like the archetypical crime drama. Evocative of the outlaw mythos of the Old West, Tommy rides across a smoky, industrialized landscape on the back of a black horse. A rogue element, his presence carries immediate power, causing pedestrians to hurriedly clear a path. You get the sense that he does not conform to this time or era, nor does he abide by the rules of society. Set in the decades between World War I and II, Peaky Blinders differentiates itself from its peers, not just because of its distinctive, almost Shakespearian style of storytelling, powerful visual style, and use of contemporary music, but also in the manner in which it shows that society provokes the very criminality it attempts to vanquish. Moreover, it dedicates time to demonstrating why this form of criminality is sometimes the only option for success in an unfair system. When the law wants to keep you relegated to the station in which you were born, success almost inevitably means breaking the rules. Tommy is considered one of the most influential characters of the decade because of the manner in which he embodies this phenomenon, and the reason why antiheroes pervade folklore across the decades. Peaky Blinders engenders a unique level of empathy within its first episodes, in which we are not just immersed in the glamour of the gangster lifestyle, but we are compelled to understand the background that provoked it. Tommy, who grew up impoverished and discriminated against due to his “didicoy” Romany background, volunteered to fight for his country, and went to war as a highly intelligent, empathetic young man. He returned with the knowledge that the country he had served had essentially used him and others like him as canon fodder, with no regard for their lives, well-being, or future. Such veterans were often looked down upon or disregarded by a society eager to forget the war. Having served as a tunneler – regarded to be the worst possible position in a war already beset by unprecedented brutality – Tommy’s constant proximity to death not only destroyed his faith in authority, but also his fear of mortality. This absence of fear and deference, coupled with his incredible intelligence, ambition, ruthlessness, and strategic abilities, makes him a dangerous weapon, now pointed at the very society that constructed him to begin with. It is also difficult to critique Tommy’s criminality, when we take into account that society would have completely stifled him if he had abided by its rules. As someone of Romany heritage, he was raised in abject poverty, and never would have been admitted into situations of higher social class. Even at his most powerful, we see the disdain some of his political colleagues have at being obligated to treat someone of his background as an equal. In one particularly powerful scene, he begins shoveling horse manure, explaining that, “I’m reminding myself of what I’d be if I wasn’t who I am.” If he hadn’t left behind society’s rules, his brilliant mind would be occupied only with cleaning stables. However, the necessity of criminality isn’t depicted as positive: it is one of the greatest tragedies of the narrative that society does not naturally reward the most intelligent or gifted, but instead rewards those born into positions of unjust privilege, and those who are willing to break the rules with intelligence and ruthlessness. Each year, the trauma of killing, nearly being killed, and losing loved ones makes Tommy’s PTSD increasingly worse, to the point at which he regularly contemplates suicide. Cillian Murphy has remarked that Tommy gets little enjoyment out of his wealth and power, doing what he does only for his family and “because he can.” Steven Knight cites the philosophy of Francis Bacon as a driving force behind Tommy’s psychology: “Since it’s all so meaningless, we might as well be extraordinary.” This is further complicated when it becomes apparent that the upper class he’s worked so arduously to join is not only ruthlessly exclusionary, but also more corrupt than he’s ever been. There are no easy answers, no easy to pinpoint sources of societal or personal issues, no easy divisibility of positive and negative. This duality is something embraced by the narrative, and embodied by its protagonist. An intriguingly androgynous figure, Tommy emulated the strength and tenacity of the women in his life, particularly his mother; however, he also internalized her application of violence, even laughing about how she used to beat him with a frying pan. His family is his greatest source of strength and his greatest weakness, often exploited by his enemies who realize they cannot fall back on his fear of mortality. He feels emotions more strongly than the other characters, and ironically must numb himself to the world around him in order to cope with it. Tommy is not a traditional hero, but the tragedy of Peaky Blinders is that he used to be, as a young man before and during the war, before realizing that all traditional heroism would have gained him and his family would be a life of drudgery and servitude at the heel of the power-bloated ruling class. Criminality is not a self-sustaining lifestyle, but in a world in which the only alternatives seem to be subjugation and corrupt authority, what other options are there? However, all hope is not lost. Creator Steven Knight has stated that his hope is ultimately to redeem Tommy, so by the show’s end he is “a good man doing good things.” There are already whispers of what this may look like: as an MP, Tommy cares for Birmingham and its citizens far more than any “legitimate” politicians, meeting with them personally to ensure their needs are met; as of last season, he attempted a Sinatra-style assassination of a rising fascist simply because it was the right thing to do. “Goodness” is an option in the world of Peaky Blinders; the only question is what form it will take on a landscape plagued by corruption at every turn. Regardless of what form his “redemption” might take, it’s negligible that Tommy will ever meet all the criteria of an archetypal hero as we understand it today. He is far more evocative of the heroes of Ancient Greece, of the Old West, of the Golden Age of Piracy, of Feudal Japan – ferocious, magnitudinous figures who move and make the earth turn with them, who navigate the ever-changing landscapes of society and refuse to abide by its rules, simultaneously destructive and life-affirming. And that’s what makes him so damn compelling. Other examples:

Antiheroes show us we can be the villains.As demonstrated by: Walter White from Breaking Bad. Why he could be a hero: He’s a brilliant, underappreciated chemist whose work contributed to the winning of a Nobel Prize. He’s also forging his own path in the face of incredible adversity, and attempting to provide for his family in the event of his death. Why he’s an antihero: In his pre-meth days, Walt failed to meet the exceptionalism associated with heroes, as a moral but socially passive underachiever living an unremarkable life. At the end of his transformation, he is exceptional at what he does, but has completely lost his moral standards. What he can teach us: G.K. Chesterton wrote, “Fairy tales do not tell children that the dragons exist. Children already know that dragons exist. Fairy tales tell children the dragons can be killed.” Following this analogy, it is equally important that our stories show us we, ourselves, can be the dragon. Or the villain, to be more specific, because being a dragon sounds strangely awesome. Walter White of Breaking Bad is a paragon of antiheroism for a reason: he subverts almost every traditional aspect of heroism. From the opening shots of Walt careening along in an RV, clad in tighty whities and a gas mask, we recognize that he is neither physically capable, nor competent in the manner we’ve come to expect from our heroes. He is not especially conventionally attractive, nor are women particularly drawn to him. He does not excel at his career or garner respect. As the series progresses, Walt does develop the competence, confidence, courage, and resilience we expect of heroes, but he is no longer the moral protagonist: he is self-motivated, vindictive, and callous. And somehow, he still remains identifiable, which is integral to his efficacy. But let us return to the beginning of the series, and talk about how, exactly, Walt subverts our expectations from the get-go. Walt is the epitome of an everyman: he’s fifty years old, middle class, passive, and worried about identifiable problems – his health, his bills, his physically disabled son, and his unborn baby. Whereas Tommy Shelby’s angelic looks, courage, and intellect subvert our preconceptions about what a criminal can be, Walt’s initial unremarkability subverts our preconceptions about who can be a criminal. The hook of the series is the idea that a man so chronically average could make and distribute meth. Just because an audience is hooked by a concept, however, does not mean that they’ll necessarily continue watching. Breaking Bad could have easily veered into ludicrosity, if it weren’t for another important factor: character. Walt is immediately and intensely relatable, and he somehow retains our empathy for the entirety of the series, even at his least forgivable. When we first meet Walt, his talents are underappreciated, he’s overqualified for his menial jobs, chronically disrespected by everyone around him, underpaid, and trapped in a joyless, passionless life in which the highlight of his day is a halfhearted handjob from his distracted wife. And to top it all off? He has terminal lung cancer. Happy birthday, Walt. We root for him for the same reason we root for Dumbo, Rudolph, Harry Potter: he’s an underdog. The odds are stacked against him, and we want to see him triumph. Which is why it’s cathartic, for us and for Walt, when he finally finds a profession in which he can excel – even if that profession is the ability to manufacture incredibly high-quality meth. His former student Jesse Pinkman – a character so interesting that there’s a genuine risk he’ll hijack this essay – appreciates his skill, and this early appreciation is what makes his relationship with Jesse feel so much more genuine than Walt’s relationship with his family, even as their dynamic becomes increasingly unhealthy and Walt uses Jesse to bolster his meth business and his ego. This deeply dysfunctional but heartfelt father-son connection is Walt’s tether to humanity as he becomes increasingly inhumane, while also demonstrating his descent from morality. It has been pointed out that one can gauge how far-gone Walt is from his moral ideals by how much Jesse is suffering. But to return to the initial point, it is imperative that we first empathize with Walt in order to adequately understand his descent. Aside from the fact that almost all characters are more interesting if the audience can or wants to empathize with them, Walt’s relatability makes it easy to understand our own potential for toxic and destructive behaviors. We are the protagonist of our own story, but we aren’t necessarily its hero. Similarly, we understand how easily we can justify destructive actions, and how quickly reasonable feelings of anger and injustice swerve into self-indulgent vindication and entitlement. Walt claims to be cooking meth to provide for his family, and this may be partially true; but he also denies financial help from his rich friends out of spite, and admits later to his wife Skylar that he primarily did it for himself because he was good at it and “it made (him) feel alive.” This also forces us to examine our preconceptions, and essentially do Walt’s introspections for him: whereas Peaky Blinders emphasizes the fact that Tommy and his family would never have been able to achieve prosperity by obeying society’s laws, Walt feels jilted out of success he was promised by a meritocratic system that doesn’t currently exist. He has essentially achieved our current understanding of the American dream – a house with a pool, a beautiful wife and family, an honest job – but it left him unable to provide for his wife and children or even pay for his cancer treatment. He’s also unhappy and alienated from his passions and fellow human beings. With this in mind, it’s understandable – if absurd – that the only way he can attain genuine happiness and excel is through becoming a meth cook. In this way, Breaking Bad is both a scathing critique of our current society, and a haunting reminder that there’s not as much standing between ourselves and villainy as we might like to believe. So are we all slaves to this system of entitlement and resentment, of shattered and unfulfilling dreams? No, because Breaking Bad provides us with an intriguing and vital counterpoint: Jesse Pinkman. Whereas Walt was bolstered with promises that he was gifted and had a bright future ahead of him, Jesse was assured by every authority figure in his life that he would never amount to anything. However, Jesse proves himself skilled at what he’s passionate about: art, carpentry, and of course, cooking meth. Whereas Walt perpetually rationalizes and shirks responsibility, Jesse compulsively takes responsibility, even for things that weren’t his fault. Whereas Walt found it increasingly acceptable to endanger or harm bystanders, Jesse continuously worked to protect innocents – especially children – from getting hurt. Though Jesse suffered immensely throughout the course of the show – and the subsequent movie, El Camino – the creators say that he successfully made it to Alaska and started a carpentry business. Some theorists have supposed that Jesse might be a Jesus allegory – a carpenter who suffers for the sins of others. Regardless of whether this is true, it is interesting, and amusing to imagine Jesus using the word “bitch” so often. Though he didn’t get the instant gratification of immediate success that Walt got, he was able to carve (no pun intended – carpentry, you know) a place for himself in the world. Jesse isn’t a perfect person, but he reminds us that improving ourselves and creating a better life is an option, even if Walt’s rise to power was more initially thrilling. So take heart: there’s a bit of Heisenberg in all of us, but there’s also a bit of Jesse Pinkman. Other examples:

Antiheroes emphasize the absurdity of contemporary culture.As demonstrated by: Marty Byrde from Ozark. Why he could be a hero: He’s a loving father who ultimately just wants to provide for and ensure the safety of his family. He’s also fiercely intelligent, with excellent negotiative, interpersonal, and strategic skills that allows him to talk his way out of almost any situation without the use of violence. Why he’s an antihero: He launders money for a ruthless drug cartel, and has no issue dipping his toes into various illegal activities. Why he’s compelling: Marty is an antihero of the modern era. He has an uncanny ability to talk his way into or out of any situation, and he's a master of using a pre-constructed system of rules and privileges to his benefit. In the very first episode, he goes from literally selling the American Dream, to avoiding murder at the hands of a ruthless drug cartel by promising to launder money for them in the titular Ozarks. Despite his long history of dabbling in illegality, Marty has no firearms – a questionable choice for someone on the run from violent drug kingpins, but a testament to his ability to rely on his oratory skills and nothing else. He doesn’t hesitate to engage an apparently violent group of rural thieves to request the return of his stolen cash, because he knows he can talk them into giving it back to him. The only time he engages other characters in physical violence, he immediately gets pummeled, because physical altercation has never been his form of currency. Not that he’s subjected to physical violence particularly often, either: Marty is a master of the corporate landscape, which makes him a master of the criminal landscape. He is brilliant at avoiding the consequences of his actions. It’s easy to like and admire Marty for his cleverness, for being able to escape from apparently impermeable situations with words as his only weapon. He’s got a reassuring, dad-ly sort of charisma that immediately endears the viewer, and offers respite from the seemingly endless threats coming from every direction. He unquestionably loves his family, including his adulterous wife. As such, it’s easy to forget that Marty is being exploited by the same system that exploits all of us: crony capitalism. The polar opposite of meritocratic capitalism – in which success is based on hard work, ingenuity, and, hence the name, merit – crony capitalism benefits only the conglomerates that plague the global landscape like cancerous warts, siphoning money off of workers and natural capital, keeping them indentured with basic necessities and the idle promise of success. Marty isn’t benefiting from his hard work in the Ozarks. Everything he makes goes right back to the drug cartel who continuously threatens the life of him and his family. He is rewarded for his efforts with a picturesque house, a boat, and the appearance of success, but he is not allowed to keep the fruits of his labor. Marty may be an expert at navigating the corporate and criminal landscape, but it still exploits him. In this manner, Marty embodies both the American business, the American worker, and a sort of inversion of the American dream. In this same manner, Marty, the other characters, and even the Ozarks themselves embody the modern dissonance between appearance and reality. Marty’s family looks like something you’d respect to see on a Christmas card from your DILF-y, successful coworker, but it’s bubbling with dysfunctionality. His wife is cheating on him with a much-older man, and instead of confronting her about it, he first hired a private investigator and then spent weeks rewatching the footage, paralyzed with options and debating what to do. The problem somewhat solves itself when his wife’s lover is unceremoniously murdered by the cartel, and Wendy and Marty are driven into a sort of matrimonial business partnership motivated by the shared interest of protecting their children, but this also further demonstrates how corporate even their family dealings have become. His children, though precocious, are forced to contend with age-inappropriate levels of responsibility and the trauma of sudden relocation, juxtaposed with a childhood of complete privilege up until this point. Conversely, the shadow of the Byrde family is arguably the Langmores. Precocious teenagers Ruth and Wyatt can initially be shrugged off as local hillbillies and budding con-artists, but much like the Shelby family of the Peaky Blinders, they prove to be extremely intelligent individuals suffering beneath a society that doesn’t care about their stifled potential. Systemic poverty is a bushfire that spreads from one generation to the next, stoked by the prejudices of authority figures and abusive parental figures who refuse to embrace change out of a misguided sense of class-loyalty. Almost every other character we meet eventually inverts our expectations of them: from the folksy, salt-of-the-earth farmers who grow poppies for opium and murder more remorselessly than the cartel itself, to the cookie-cutter FBI agent whose behavior becomes increasingly volatile and chaotic, to the heroin-filled Bibles handed out by an unknowing preacher, to the secrets hidden by the lake itself, every detail conveys corruption hidden behind a postcard-pretty picture of tranquility and success. Marty’s awareness of this illusion, and what lurks behind it, is perhaps the greatest subversion of all. Marty knows that the world of appearance and the world of reality coexist, and he was blessed with a natural talent for navigating within the two. Like Walter White, Marty makes us question our assumptions about who a criminal can be – despite the fact that many successful, attractive, middle-aged family men launder money and juggle criminal activities, it’s still jarring to witness, which tells us something about how image informs our understanding of reality. Socially privileged, white-collar criminals simply have more control over how they’re portrayed than an inner-city gang, or impoverished teenagers. However, unlike Walt, Marty’s criminal activities are not any kind of middle-aged catharsis: they’re a way of life, firmly ingrained in the corporate landscape. They were present long before he arrived on the scene, and he knows it. He just has to navigate them.

Just like our shining, messianic heroes can teach us about truth, justice, and the American way, so too does each antihero have something to teach us: they teach us that society doesn’t reward those who follow its instructions, nor does it often provide an avenue of morality. Even if you live a life devoid of apparent sin, every privilege is paid for by someone else’s sacrifice. But the best antiheroes are not beacons of nihilism – they show us the beauty that can emerge from even the ugliest of situations. Peaky Blinders is, at its core, a love story between Tommy Shelby and the family he crawled out of his grave for, just as Breaking Bad is ultimately a deeply dysfunctional tale of a father figure and son. Ozark, like its predecessors, is about family – the only authenticity in a society that operates on deception, illusion, and corruption. They teach us that even in the worst times and situations, love can compel us, redeem us, bind us closer together. Only then can we face the dragons of life, and feel just a bit more heroic. Other examples:

I’ve been getting a lot of asks about writing horror lately, and I’d like to take the time to answer all of them! But for now, I wanted to share my top tip for evoking fear in the reader.

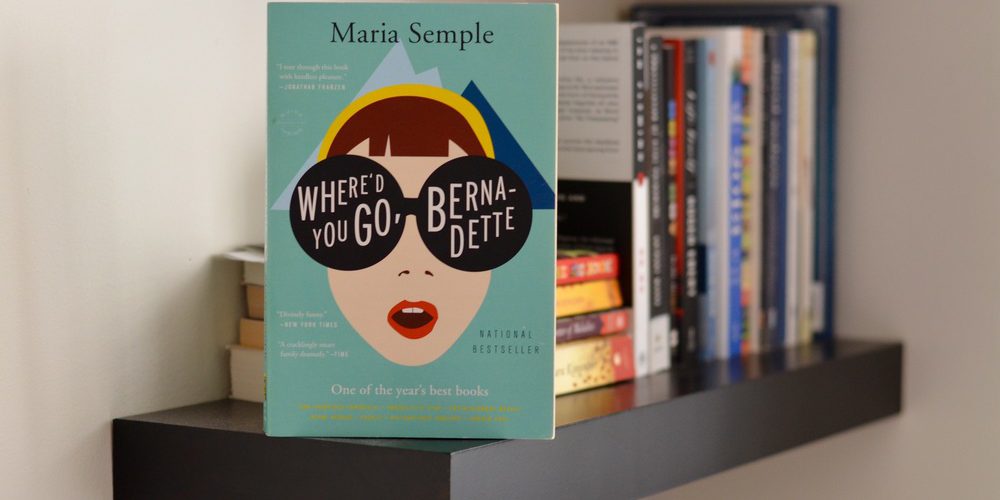

Keep in mind, I am not a horror writer by trade, but I utilize it a lot in my stories – particularly those of the magical realism variety – and I am a huge fan of the horror genre. This is what I’ve learned: Your most important tool is the reader’s imagination. How many times have you been absorbed in a horror movie, adrenaline pumping and watching, enraptured, through your fingers, only to be smacked back to reality by a goofy monster design or ludicrous backstory? Some of the best, and most memorable horror fiction and media, on the other hand, understand the power of what they don’t show you. I’m not the biggest fan of Blair Witch Project – or how it treated its cast – but it earned back over 248 million dollars within its eight days against a $60,000 budget and remains solidified in the minds of countless viewers. It is, undeniably, an effective and memorable piece of media, largely thanks to what they do and don’t show us. What they show us: local lore, the character’s reactions and escalating fear, an admittedly haunting and ambiguous ending, a shitload of trees. What they don’t show us: the monster. Not only do we not see the monster, but we don’t see its motivations, its backstory. We don’t know what it is. We don’t know what it wants. And that’s terrifying, for us and for the characters. Now, let’s look at a personal favorite of mine: Coraline, both the book and the amazing movie. “But Caff,” you say, “Coraline isn’t a horror movie! It’s a fantasy, adapted from a children’s book!” To which I say, you are wrong. Coraline is the scariest shit I have ever seen in my life. Everyone who wants to write horror should read and watch it. What makes the Other Mother such a viscerally horrifying threat? Is it the fact that she preys on vulnerable children, and has been doing so for over 150 years? Okay, probably. But: just as important is the fact that that’s the only thing we know about her. We don’t know where she came from, how she came to be. She’s never weighed down or humanized by a backstory. We only know her threat to Coraline, her power, and what she’s done to children in the past. And that’s scary as fuck. This is also the reason why masks are such an effective tool in horror. For one thing, it literally puts you in the shoes of the character, who is as blind to the antagonist’s true nature and intentions as you are. And, just as importantly, it invokes the imagination of the reader. Because what we can imagine – or try to imagine – is almost always scarier than the fact, in fiction or otherwise. I hope this helps, and happy writing! <3 thecaffeinebookwarrior.tumblr.com/post/184945283175/my-1-tip-for-writing-horror Learning of the objective correlative is like learning a new word. Once you know what it means, you start to see it everywhere. I learned of this literary gem during my last grad school residency. As defined by Merriam-Webster, an objective correlative is, “something (such as a situation or chain of events) that symbolizes or objectifies a particular emotion and that may be used in creative writing to evoke a desired emotional response in the reader.” Most of my writer peeps have probably, unknowingly, used objective correlatives in their own work. I know I have. And if you’ve picked up a book within the past decade, than you’re at least familiar with one or two. Don’t believe me? Here are a few examples of famous objective correlatives. "The Raven," by Edgar Allan Poe(Image source.) Here’s an easy one. The objective correlative, in this case, is Poe’s titular corvid, who represents grief, loss, and hopelessness. The bird visits the nameless protagonist “once upon a midnight dreary” while he ponders the death of his beloved, “the rare and radiant maiden whom the angels name Lenore.” When his asks his winged visitor if he will see Lenore in the afterlife, the bird merely replies, “Nevermore.” It embodies his sorrow, loss of faith, and fear that they will never be reunited. Life of Pi, by Yann Martel(Image source.) Can you guess? In this case, the objective correlative is our boy Richard Parker, the oddly named tiger who accompanies Pi on his lone voyage. Richard represents Pi himself, while their journey alone in a lifeboat represents Pi’s spiritual journey. A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, by Betty Smith(Image source.) First off, I highly recommend everyone read this book – especially everyone who thinks The Classics™ are reserved to the angsty male protagonists who were shoved in your face during high school. A Tree Grows in Brooklyn does not fuck around: it deals with poverty, classicism, drug addiction, female sexuality and sexual autonomy, and an assload of complex, flawed, strong-as-hell female characters. And it was written in 1943. Do yourself a huge-ass favor, and read A Tree Grows in Brooklyn. Anyhoodle. The tree in question is the Tree of Heaven, growing outside of Francie Nolan’s window. Though the tree is considered a nuisance, and was chopped down several of times, it continues to grow. The tree represents Francie’s determination to survive, grow, and better herself, in spite of the destitution in which she grew up. The Great Gastby, by F. Scott Fitzgerald(Image source.) Speaking of angsty male protagonists, let’s have a look at one of the angstiest of them all. This is a pretty famous example, so see if you can figure it out. Give up? It’s the green light. The green light represents Gatsby’s longing for Daisy. Where'd You go, Bernadette, by Maria Semple(Image source.)

Let’s conclude by moving away from objective correlatives which are, you know, objects. In this case, Bernadette has literally disappeared into her role as a wife and a mother. She has completely lost her sense of identity, which is represented by her physical disappearance. So, why should you care? Simple! The objective correlative is a great tool. It conveys emotions in a far more organic and powerful way than simply hitting the reader over the head with them. Imagine if “The Raven” was just a poem about some dude feeling sad and grieving his dead girlfriend. No ravens to be seen. That would be a total bummer, it would immediately make the title grievously misleading, and no one would probably remember it. Or if Life of Pi was just a story of a kid trying to survive in a lifeboat, alone, for over 150 pages. That would be just plain bleak, and a lot less exciting, interesting, or memorable. The tree in Tree Grows in Brooklyn emphasizes Francie’s struggle, and enhances the emotional poignancy of the narrative. The moment when it occurs to us that Francie is the tree, growing upwards in the face of adversity, is far more powerful than having it simply spelled out to us. In many cases, the objective correlative is the physical conflict that represents the emotional conflict, as in the case of Where’d You Go, Bernadette – without it, there would simply be no book. So next time you read a book, make sure you have a pen in your hand – I always do – and see if you can spot the objective correlative. As with any literary tool, the more you read about them, the more they can work for you! I hope this helps, and happy writing! |

About the AuthorBrooksie C. Fontaine was accepted into college at fifteen and graduate school at nineteen. She has an MFA in English, and is currently completing a second MFA in Illustration. Archives

March 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed