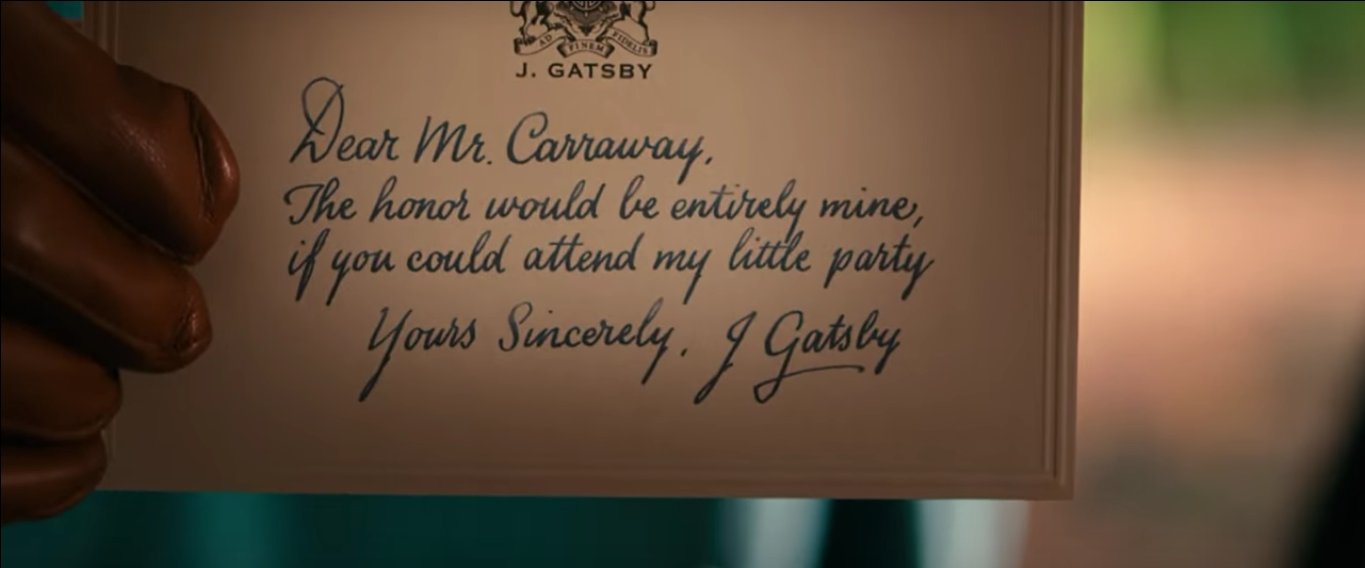

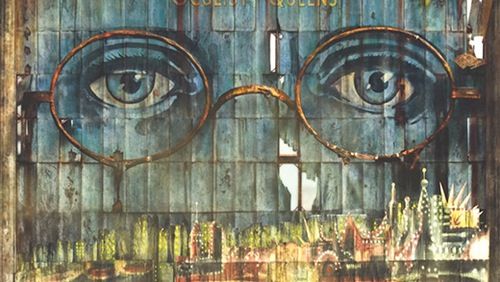

Introduction In my younger and more vulnerable years, my father gave me some advice that I’ve been turning over in my mind ever since. “Whenever you feel like criticizing any one,” he told me, “just remember that all the people in this world haven’t had the advantages that you’ve had.” So opens one of my all-time favorite works of literature, a richly written book with prose that’s bright and dark and begs to be consumed in gulps. It is, in many ways, a tone-setter for the pages to come: the book is often a rumination on various degrees of advantage – or rather, on class, wealth, and the distinction between the two. On Old Money, and the suspicion with which Old Money regards New Money – despite the fact that all Old Money was once New Money, and initially amassed itself through similarly unscrupulous means. Only time provides it with the illusion of cleanliness. The book is also preoccupied with appearances, and the manner in which we cast the spotlight of judgment on others. All of this is alluded to in the first few words of the book. It is also a somewhat humorous opening line, in the context that its narrator, Nick Carraway, spends the rest of the book criticizing and judging everyone around him. I can think of few literary burns so searing as, “one of those men who reach such an acute limited excellence at twenty-one that everything afterward savors of anticlimax.” “He peaked in college” simply does not have the same ring to it. Nick is a judgmental person, and it’s through his judgements that we form our own assessments of the world around him. This, in and of itself, is not a criticism of Nick. Though he’s far from perfect, I like Nick – he feels like my guide through a titanic world of larger-than-life figures that would otherwise be overwhelming, as Virgil was to Dante. For this reason, despite his own flaws, Nick has been the recipient of a fair degree of affection from readers. If anything, his subtly scathing view of the other characters only stokes our sense of camaraderie towards Nick. The Great Gatsby is a book full of absurd rich people making poorly thought-out, careless choices, and the narrative is somewhat contingent on the fact that we’re aware of that. Just as it’s contingent on humanizing them to a degree, and alluding to inner complexities of their own that even Nick’s wry observations can’t perceive. I tinkered with a few prospective titles for this piece. The Great Gatsby: A Failed American Dream, The Great Gatsby: Dehumanization Through Symbolism, and The Great Gatsby: An Ode to the Fleeting Past, were a few that came to mind. The Great Gatsby: Literature’s Best Drunk Driving PSA was a briefly considered fourth option. But ultimately, Gatsby is too thematically multifaceted to reduce my interpretation of it to a single theme. So I’ll break them down, one by one, and how they form the foundation on which the novel is built. A Failed American DreamDefined by the Oxford English Dictionary as “the ideal that every citizen of the United States should have an equal opportunity to achieve success and prosperity through hard work, determination, and initiative,” the American Dream is as ripe for rumination as it is for pursuit. The American Dream is ultimately that of a meritocracy, in which anyone, regardless of background, can achieve their goals and socially ascend if they’re hard-working and qualified. Importantly, the thesis of The Great Gatsby has nothing to do with whether or not the American Dream is possible to achieve for anyone, and instead focuses on the specific manner in which its central characters fail to achieve it – and demonstrates that though we may have won independence from the British, we’ve never quite shaken the ideals of the aristocracy. Gatsby bears the title of the book for a reason, and it has very little to do with Gatsby’s most authentic traits as a person. If it were truly about Gatsby the man, it wouldn’t even be called Gatsby, but Gatz – referring to James Gatz, Gatsby’s real name. Though I have no proof for this, I do maintain that the stolen name of Mad Men’s Don Draper – who, in many ways, embodied the American Dream as it was incarnated throughout the 1960s – was inspired by Gatsby’s spur-of-the-moment decision to change his name. Though unlike Draper, who stole his fallen comrade’s name to escape gruesome combat conditions, Gatsby changed his name only to fit the lofty ideals he held for himself and the drudgery of his social class. The truth was that Jay Gatsby of West Egg, Long Island, sprang from his platonic imagination of himself. He was a son of God (...) and he must be about His Father’s business, a service of vast, vulgar, and meretricious beauty. In terms of his mortal mother and father, Gatsby was begotten by “farm people” whom “his imagination had never really accepted” as his parents. He was frustrated by them, by his attempts to attend college (which required working as a janitor – work he viewed as beneath his grand ideals), and by his early encounters with women, towards whom he was “contemptuous (...) of young virgins because they were ignorant, and the others because they were hysterical about things which in his overwhelming self-absorption he took for granted.” It is an interesting contrast to his later obsession with Daisy, though as I’ll elucidate later, I doubt his self-absorption ever truly waned; rather, Daisy became a part of his grand vision for himself. Progressing further into the novel, I’m inclined to believe this has to do with class, because he had no such qualms with Daisy – the first “nice” (or rather, rich) girl to let him into her life, and he appears just as enamored by her house and her lifestyle as he is by her. Gatsby, to an extent, appears to be aware of this. When Nick speculates on what it is that makes Daisy’s voice so magical, Gatsby replies, seemingly to his own surprise, that the magic in her voice was “money.” The problems with heaping such vast amounts of personal symbolism on a human being will be discussed shortly. Suffice it to say, Gatsby may have had lofty aspirations since childhood, but Daisy became the pillar around which he built them. The entire persona of Jay Gatsby became dedicated to what he perceived Daisy to be: after buying a mansion across from hers, he threw wild parties in the hopes of enticing her, and then stopped them just as abruptly when he decided she didn’t like them. Nick describes Gatsby’s persona, though charismatic to pull it off, as a borderline parody of aristocratic mannerisms. Gatsby made Daisy into a goddess, and his life into her temple. Before we get too far down the rabbithole of ascribing symbolism to human beings – I have an entire section dedicated to that – let’s return to Gatsby’s relationship with the American Dream. On a surface level, he is a tremendous success story: even if his wealth was the result of some affiliation with organized crime, the fact remains that Gatsby was the child of impoverished farmers who dreamed his way into a lavish mansion and a life of decadent parties, full of movie stars, politicians, gangsters, and financial moguls of every caliber. In his pink suit and gilded-yellow car and shining mansion, Gatsby seems to encapsulate the American ideal that anyone can become someone. For all his greatness, however, Gatsby failed to achieve true prosperity. His funeral was attended only by his father, by Nick, and by a nameless owl-eyed man whose round spectacles evoke the all-seeing gaze of T.J. Eckleburg (a.k.a. God – his other Father, as Nick alluded to with Gatsby’s “platonic conception of himself”). In other words, though Gatsby achieved riches and fame, he remained impoverished with regards to love, authenticity, and genuine connection. All the other main characters illustrate similarly flaccid fulfilments of the American Dream. Daisy and Tom Buchanan were born into the kind of life Gatsby wanted, and both had something that he could never earn: Old Money. Though wealth can be accumulated, the class difference remains impermeable – described in the book as a “sheet of barbed wire.” And yet, Daisy and Tom are miserable people. Daisy is fully aware her husband is cheating on her, and feels, on some level, deeply unsatisfied with her life. Within pages of her introduction, she sadly remarks that the best thing a woman can be is a “beautiful little fool.” She says this with regards to her daughter, whose birth Tom is implied to have missed while he was out having a tryst. As for Tom, he is deeply insecure, and makes it everyone else’s problem. He alludes, at various points, to being jealous of Gatsby, and even more explicitly is threatened by the very existence of people of color – he makes derogatory reference to The Rise of the Colored Empires within a few pages of his introduction, and later makes an equally perplexing reference to interracial marriage while disparaging Gatsby and Daisy’s affair (especially strange, since Gatsby and Daisy are both white, as Jordan Baker sheepishly points out). Tom was born into money and social privilege of every kind; he has nothing upon which to build his self-esteem other than the way he was born. And he clings to it, this notion of inherent superiority based only on his race and class – because he really doesn’t have anything else upon which to base his identity. Of course, because they were born into wealth, the Buchanans might be disqualified from pursuit of the American Dream to begin with, because they have very little to aspire towards. They were born at the top of the social food chain, and it’s no coincidence that both of their lower-class lovers have been killed by the end of the book while they, as Nick puts it, “retreat back into their wealth.” But even if they had done anything to earn their status, could they truly be considered prosperous? They’re practically bankrupt when it comes to maturity, self-worth, and true joy. Nick himself concludes his final interaction with Tom with the realization that he’s talking to a giant child, who’s never truly had to face consequences or overcome obstacles. Nick himself has a complicated relationship with the American Dream. He hasn’t given up on achieving prosperity, but he certainly has become disillusioned by the brand of prosperity represented by New York and its Old and New Money. In the short term, he has given up his attempts to achieve success as a New York bond salesman, and resolved to return West – from which he, Daisy, Tom, and Gatsby all originally hailed. I won’t be touching on Jordan Baker’s relationship with the American Dream, though not for lack of interest – only for lack of conclusive knowledge. Jordan is one of my favorite characters, and though we find out little about her inner life, we get the sense that she has a complex internal world beneath her aloof, feline exterior. Returning to the other characters, whom we get to know somewhat more conclusively, it could be that none of them were pursuing the right things, and had the wrong definition of prosperity. Money isn’t meaningless, but happiness seldom comes from assigning superiority exclusively to wealth, and defining betterment exclusively as the accumulation of it. The Great Gatsby is aware that there’s more to life than decadence and wealth. In one of the most subtly impressive elements of the book, Fitzgerald makes a billboard into a character, and curiously, one of my favorite characters; from the industrial area dubbed “the City of Ashes,” the spectacled blue eyes of T.J. Eckleburg are all seeing, and represent the eyes of God. A reminder that past the facade of luxury, there exists right, wrong, and truth. And beneath the layers of symbolism that envelop each character, there exists a flawed and multifaceted human soul. Dehumanization Through SymbolismThe Great Gatsby is full of symbolism. Almost everything represents something else. We all know T.J. Eckleburg is God, but the green light is also Daisy, and Daisy is the American Dream – at least, she’s the American Dream to Gatsby. By the end of the book Gatsby has become Nick’s green light – representing, to Nick, a dream so pure and unattainable that the world had to kill it. And of course, the green light is green for a reason – it represents money, the kind of inherited wealth that Gatsby so admires. Complicating things further, throughout much of the novel, Gatsby is his house, built recently but designed to look old, in the same way Gatsby’s extravagance tries to impersonate old money. This is all well and good as a reader, but it’s problematic to ascribe this much symbolism to people within your own life. Which is what the characters – especially Gatsby – are doing, all the time. In Gatsby’s case, he mythologizes human beings to the point of his own downfall. To be clear: there is something to admire about Gatsby, something appealing about a farm boy who dreamed his way out of the dust and dirt and into a glorious new life of explosive parties and extravagance of every kind. If that life feels like a dream, it’s because it is one – Gatsby’s dream, which he summoned up and walked into. We like wily, ambitious, class-hopping protagonists. Look how audiences reacted to Don Draper, whom I touched on earlier as a spiritual cousin to Gatsby, or Tommy Shelby of Peaky Blinders, who came from his own Valley of Ashes and whose spectacled blue eyes coincidentally look exactly like those of T.J. Eckleburg. We all know on some level that society wants to confine us, to homogenize us, and we root for people who are clever and perseverant enough to defy its boundaries. However, this vision is only admirable when applied to oneself. You can’t dream other people into what you want them to be, or make them into a dream that doesn’t reflect who they are. This is exactly what Gatsby does for Daisy, by making her into his symbolic green light and dedicating his worship to her without ever stopping to consider Daisy the human being. Daisy is no saint – she’s feeling insecure in her relationship, and by the end of the book, that’s somehow led to a body count of three people. My girl has problems of her own. But Gatsby’s love for Daisy is far from selfless. I refute the interpretation that Gatsby built his life and persona for Daisy – he already had grand ambitions for himself, since before he even christened himself Jay Gatsby as a teenager, and Daisy only became the living embodiment of them. I would argue that if he hadn’t chosen her as his object of worship, he would have found someone or something else to embody his dreams of wealth. Tom is an unfit husband in many ways – a serial adulterer, prone to “little sprees,” as he calls them. However, we never see any indication that Tom’s wayward nature is a primary motivation for Gatsby rekindling his relationship with Daisy, or that his greatest concern is making sure she’s happy. He never even appears to take into consideration the well-being of Daisy’s preschool-age daughter; when briefly confronted with the child, he seems baffled by her existence. Complicating things further, the little girl asks for her father – indicating that she does have some kind of a bond with Tom, as poor a role model as he may be. Neither Daisy nor Gatsby seem to consider her, even as collateral damage in their affair. Back to Gatsby’s relationship with Daisy, it struck me that when describing what made Gatsby fall in love with Daisy, much of what he described was her house and her lifestyle. Her wealth seems to be one of the few barriers between her and the annoyance with which he regarded his other feminine conquests. When they first met, he enjoyed how many men had been with her before – it “increased her value” in his eyes – but he seems disgusted by her relationship with Tom, and insistent that Daisy tell Tom that she never loved him. He doesn’t just want her love, he wants to be the only man she ever loved. For her to be an object of universal male desire, but to be the only man she’s ever desired in return. This insistence leads Daisy to push back against Gatsby and assert that she did (and does) love Tom. “Oh, you want too much!” she cried to Gatsby. “I love you now – isn’t that enough? I can’t help what’s past.” She began to sob helplessly. “I did love him once – but I loved you too.” Gatsby’s eyes opened and closed. “You loved me too?” he repeated. Though Daisy hasn’t always given Gatsby what he’s wanted, it’s one of the few times she’s verbally contradicted him. This realization, that Gatsby is not the sole recipient of Daisy’s love, is in my opinion equally as baffling to Gatsby as the realization that Daisy HAS feelings of her own. That those feelings are sometimes unpleasant to him, or contradict what he might want from her. Of course, to be fair to Gatsby, this realization is accompanied by the more understandably unpleasant sensation that Daisy isn’t actually going to leave Tom. Up until this point, the reader, Gatsby, and Nick could understandably view this as a love story, in which formerly star-crossed sweethearts have the chance to reconnect. But this conversation comes with a reversal of fortune, in which everyone in the room (along with the reader) seems to realize the truth: that Daisy and Tom aren’t going to split up, at least not on Gatsby’s account. Daisy isn’t entirely committed to being with Gatsby, and though she clearly does have genuine feelings for him, the whole thing starts to feel more like a revenge-fling against her cheating husband. Though, importantly, we have no way of knowing – Nick has long talks with Gatsby, but few with Daisy. At least, few conversations revealing enough to disclose her true feelings and motivations. We see her through Nick’s eyes, who sees her largely through Gatsby’s eyes, and never through her own. This doesn’t mean Daisy is exempt from her own crimes. She did kill a woman, a crime for which she didn’t take responsibility. This, in turn, cost Gatsby his life. George, Gatsby’s murderer, takes his only life shortly afterwards. As Nick points out, she and Tom can always take refuge in the fortress of their generational wealth and status – and they do, while three people die as direct and indirect results of their carelessness. This isn’t entirely Daisy’s fault though, or even Tom’s. Daisy’s infamous hit-and-run appears to have been an accident, and to our knowledge, Tom never finds out that his wife was the killer and not Gatsby. The novel is similarly aware that Daisy could never have lived up to Gatsby’s expectations for her – from the moment they reconnected, she was doomed to fail him. He was culpable in his own downfall, simply by placing another human being on such a gilded pedestal. Gatsby isn’t the only character who mythologizes people. Nick mythologizes Gatsby – the book itself, which is implied to be written by Nick in-universe, is called The Great Gatsby, for a reason, and not The Okay Gatsby, or This Guy I Knew A Couple Years Ago, or Rich People Wilding Out. We’re mythologizers by nature; we mythologize people, places, and things, and The Great Gatsby serves as both a celebration of this tendency and as a cautionary tale. At its core, The Great Gatsby is a nesting doll of mythologization. Nick mythologizes Gatsby who mythologizes Daisy, but who really most of all mythologizes money, and even more than that, mythologizes the past and longs more than anything to repeat it and do it right this time. An Ode to the Fleeting PastYou don’t start writing about an experience until it’s already over – or at least, in the rearview window. The book itself is set in 1922 but was published in 1925 – by the time it hit the shelves, the earliest years of the Roaring Twenties were already past. Even in the context of the story, the characters reflect on the fact that their most carefree years are behind them – Nick has a moment of panic at the realization that he’s turned thirty, and Daisy, in the same scene, contemplates that if they were truly young, they’d have started dancing to the jazz music playing from the room below. To be clear, these characters are young. Thirty is young. And I’m not saying that to console myself – as I write this, I’m only twenty-four. And even I can see that thirty is young. But what thirty is not, is a child. It is not a teenager, or those years in your twenties where it’s still somewhat acceptable to act like one. All of these characters, especially the married ones, have responsibilities. Daisy and Tom even have a child, as scary as that may be. They can no longer act like they did five years ago, when Daisy and Gatsby were first in love, and with each passing year, that relatively carefree existence must look like more of a shining memory. Almost everyone idealizes the past to a certain extent. A summer we’re nostalgic for, a look we wish would come back into fashion, a chance to do it all over, a desire to shrink back into childhood and have your mother handle your bills and bring you cookies and milk. More broadly, we as a culture worship at the altar of youth. Twenty-four-year-olds playing seventeen-year-olds sell us an idealized, airbrushed version of teenhood. Countless films, books, and television shows have become vehicles of nostalgia for decades past. And just about everyone has people who are no longer in their lives whom they’d love to talk with again. Ironically, this yearning appears timeless. Gatsby’s greatest hubris was not in accumulating his wealth. It was not in his attempts to breach “the barbed wire” that separates social class, but in his determination to recreate the past. He boldly states as much: “I wouldn’t ask too much of her,” I ventured. “You can’t repeat the past.” “Can’t repeat the past?” he cried incredulously. “Why of course you can!” He looked around him wildly, as if the past were lurking here in the shadow of the house, just out of reach of his hand. “I’m going to fix everything, just the way it was before,” he said, nodding determinedly. “She’ll see.” Gatsby, in many ways, never matured. Nick himself reflects that Gatsby “invented just the sort (of persona) a seventeen-year-old boy would be likely to invent, and to this conception he was faithful to the end.” His inability to confront reality, to keep his feet on the ground while still reaching for the clouds, and to evolve past the vision of his teenage self – all this led to his downfall, drowning in the dreams that had buoyed him for so long. He couldn’t look at himself for who he was, couldn’t reconcile his past with his goals for the future; he couldn’t see Daisy’s flaws and continue to love her anyway; he certainly couldn’t accept that she had moved on with her life and continued on with his own. He had to have everything. As Daisy put it, he wanted too much. She yearned for the past in a similar way that Gatsby did, in her own way attempting to recreate what had come before. Tom, of course, is also terrified of a prospective future in which his race and class no longer make him automatically superior to others. Aside from his panic at turning thirty, Nick also wishes to return to the past, so he could defend Gatsby more or pay him more than the one compliment he offered him. All of the characters wish, on some level, to reclaim what was, and take shelter from the frightening unknown of the future. The Great Gatsby concludes with one of the most beautiful closing lines of all time. Its final page is full of yearning, not just for a few years ago, but for the continent as it was, when it was still untouched by settlers, when man came “face to face for the last time in history with something commensurate to his capacity for wonder.” An entirely different kind of American Dream. Gatsby believed in the green light, the orgastic future that year-by-year recedes before us. It eluded us then, but that’s no matter–to-morrow, we will run faster, stretch out our arms farther….And one fine morning – So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past. The words seem to groan under their desire to start over, to do it right this time, to cup the past and drink it. But all the while, the present is alive, ignored in favor of an idealized history, shining but untouchable behind us. ConclusionThe Great Gatsby is, perhaps more than any of this, a love story. Not between Daisy and Gatsby – or rather, not just between Daisy and Gatsby, as flawed and destructive as their relationship became – but between Gatsby and Nick.

When all the “shining hundreds” who attended Gatsby’s parties have vanished, along with Daisy back into her wealth, Nick is left behind to mourn Gatsby alone. He is still mourning him two years later, enough to write a novel-length manuscript to set the record straight and/or to make sense of what happened. In a book full of superficiality and betrayal, Nick’s feelings towards Gatsby – though not always without suspicion or annoyance or cynicism – were a current of genuine admiration that carried the reader along. By the end, it’s Nick looking out at the green light, to which he has ascribed Gatsby’s dreams. I have personal reasons to meditate on The Great Gatsby’s commentary on the past. I have my late grandfather’s copy – he gifted it to me when he was still alive, and I was too young to fully appreciate it. It was a gift I only fully received years after his passing, when I truly fell in love with it. His notes are still in the margins, and I jot down my own. His in red ink, mine in gold, the past and the present existing side by side. We can’t return to the past, but it will always exist within us, informing who we are, the earth from which our future will grow. And as the enduring beauty of The Great Gatsby proves, some things are timeless.

0 Comments

|

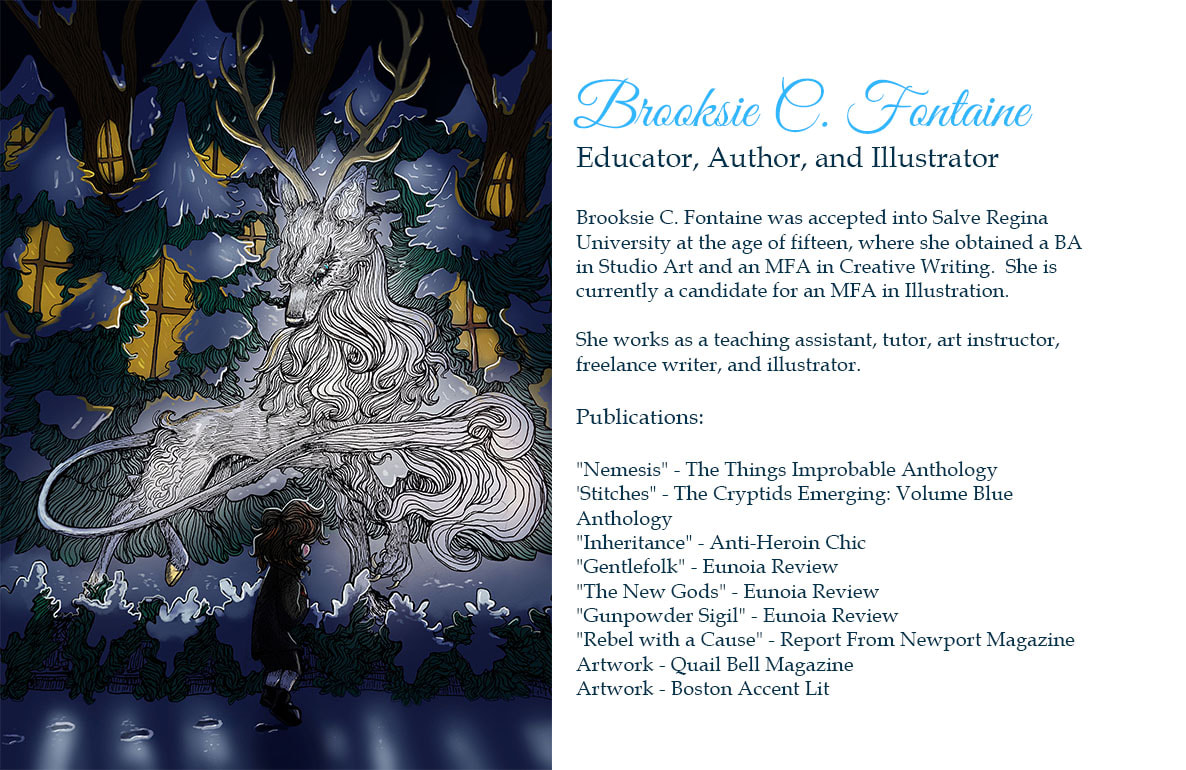

About the AuthorBrooksie C. Fontaine was accepted into college at fifteen and graduate school at nineteen. She has an MFA in English, and is currently completing a second MFA in Illustration. Archives

March 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed