|

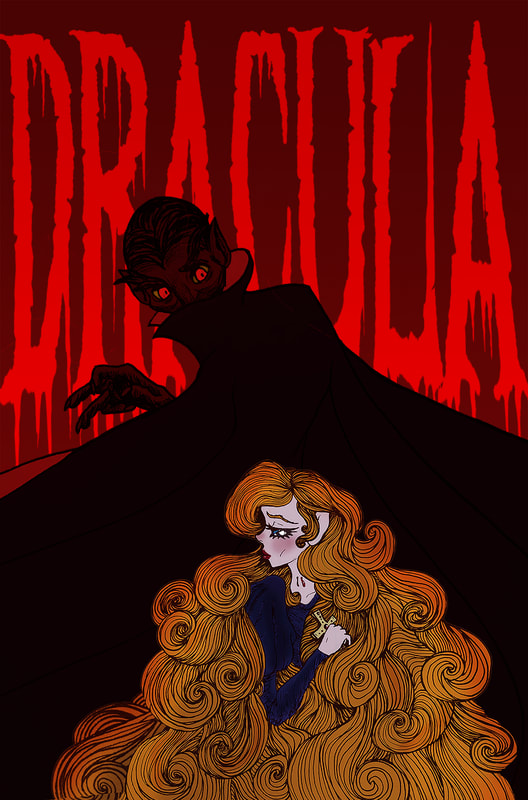

Dracula and Mina, by Brooksie C. Fontaine (me!) IntroductionMore than a century after its publication, Dracula remains an intoxicating read. Adaptations (with some exceptions) seldom capture the sense of dread the titular vampire invokes, let alone how or why. Similarly, it’s seldom acknowledged or appreciated how hopeful and warm the novel eventually becomes. Even typing it outright that Dracula is, indeed, a hopeful and warm novel feels absurd. And yet, to me, the book practically overflows with love – even love towards Dracula himself, and I’ll elaborate on how and why later. In order to explain what I mean by this, I will break my analysis into sections. To understand the salvation of Dracula, one must first understand the true source of its terror. Thus, the first section of this analysis will be dedicated to the terror of the novel, and what the antagonist represents. The second section will be dedicated to the antithesis of Dracula’s terror – that is, the love the characters develop for one another, and their faith that goodness will prevail. The Horror of DraculaBefitting a book bearing his name, Dracula assumes the spotlight for the first portion of the novel – as does everything he represents. Through the diary entries of poor Jonathan Harker – a solicitor who just wants to do his job, only to be held hostage by sadistic vampires – we experience what it’s like to be a prisoner in Dracula’s castle. For a modern reader, this initially almost comes across as rather comical: a solicitor, dedicated to doing his job even while trapped in an inhospitable and gothic domain, negotiating with a client who regularly exits the building by scaling down it “in lizard fashion.” Someone get this man a raise. Jonathan’s imprisonment, however, quickly becomes a claustrophobic, carnivorous nightmare. Dracula casually feeds a baby to his three brides, and has the mother devoured by wolves (he has a command over most carnivores). As for Dracula himself, as he is described in this original text, he is far from the dashing prince of darkness that other adaptations sometimes depict him as: there is nothing appealing about the mental visual of Dracula, flesh slightly bloated from his feast, eyes open and unseeing as he “sleeps” in an earth-filled coffin. This place – Dracula’s castle, which is really an extension of Dracula’s character – is devoid of love, warmth, and safety. Jonathan's only protection is the crucifix around his neck, gifted to him by worried locals as he traveled to Dracula’s castle. And what little solace he has comes from the thought of his betrothed, Mina, and the hope that they may be reunited. We don’t get to enjoy much of that comfort, however; for most of the first portion of the book, we really have no way of knowing if Jonathan will be alright (unless we skip ahead or read the Wikipedia summary) and we’re deprived of any other comforting or benevolent presence. As we discover later, the protagonists – Jonathan, Van Helsing, Mina, Lucy, Dr. Seward, Arthur, and Quincey – represent persevering love, warmth, affection, and faith. Dracula is the absence of that. Perhaps this, then, is the horror of Dracula: a loveless existence, driven only by the need for consumption – and, as represented by the skin-deep beauty and provocative nature of the brides, other carnal impulses, such as sexual relief. Indeed, the trauma Dracula inflicts on Jonathan, Lucy, and Mina does feel evocative of sexual trauma, and his method of attack – which involves penetration via his teeth and the exchange of fluids, often in the victim's bedroom – feels evocative of sexual violence. Other real-world horrors Dracula evokes include the abuse of peasant and working-class populations by aristocracy – Dracula literally feeds on the impoverished populations of his country, taking their children, and they have little means of recourse against the tyrannical vampire. Moreover, the illness that overcomes his victims before their death and transformation is extremely evocative of tuberculosis, which plagued Victorian society. The horror of Dracula does not end there, however. Nor does it end with the terror of Dracula’s relentless consumption, demonstrated hauntingly when he feasts on the entire crew of the ship that was unfortunate enough to unknowingly carry his coffin among its cargo. The horror of Dracula comes from the concept that Dracula’s evil is infectious. Even Dracula himself was a great man whose body was possessed by a malevolent force, which was then spread to his brides – also innocent women, possessed by an evil that feeds upon children – and which he also temporarily spread to Lucy, before her reanimated body is killed out of mercy. During the final act of the novel, Mina’s potential transformation spurs a race against time to slay Dracula, lest she transform into a vampire herself. More on that in a minute. Before any of that, however, there’s already the sense that Jonathan – a prisoner in Dracula’s castle – must adopt some of his characteristics in order to figure out his predicament and survive. Like Dracula, he scales the castle wall, first to get into Dracula’s room and then, presumably, to escape. By necessity, he must entertain violent thoughts, and be willing to act on them – to allow Dracula to continue to exist would be an evil in and of itself. Unfortunately, Dracula’s hypnotic stare prevents Jonathan from following through, even when Dracula is “sleeping” with his eyes open. The fact that Dracula dons Jonathan’s clothes to prey on the locals contributes even more to this sense of convoluted and corrupted identity. This is a precursor to the true terror of Dracula, which grows more pernicious with each of his prospective victims. Lucy’s death and reanimation raises the stakes (no pun intended) for the rest of the novel. It was terrible enough to watch the sweet, bubbly Lucy be taken by illness, Van Helsing and co. working tirelessly to save her via transfusion after transfusion, but it’s even worse when it becomes clear what she’s become: a vampire who preys on children. When the same men who struggled to save her end up mercy-killing her reanimated body, it feels like a relief. Finally, the narrative is brought full-circle with Dracula’s attempt to transform Mina Harker, who serves as the emotional core of the novel. This compels the characters to pursue Dracula to the place where the story began – his castle – and repeats some of the themes that began with Jonathan’s imprisonment: in order to defeat Dracula, Mina must become a little bit like him. Partially transformed and edging more towards vampirism by the day, Mina is able to partially follow Dracula’s actions via this unique connection. This isn’t to make it sound as though Mina girl-bosses her way to Dracula’s castle without any difficulty. The scene in which Dracula forces Mina to consume his blood is grotesque, almost too evocative of real-life violence, and Mina’s descent towards vampirism is a tense affair. When attempting to receive a blessing, the holy water burns a cross into Mina’s forehead, and she breaks down at being rendered “unclean.” To top it all off, virtually all of the characters now have trauma surrounding Dracula and vampires. I haven’t mentioned this yet, but all the male main characters except for Van Helsing and Jonathan Harker have proposed marriage to Lucy (she graciously rejected Quincey Morris and Dr. John Seward, but accepted Arthur) and all continued to dearly love her as a friend, making her death and reanimation all the more horrific. Their final confrontation with Dracula is relatively brief, but the tension leading up to it is palpable. How, then, is Dracula defeated? More importantly, how is he defeated without the main characters becoming like him? The Salvation of Dracula I’ve already covered that OG Dracula is a brutal, nasty, and frankly terrifying character. There’s no mercy or empathy to get in the way of his appetite, his shapeshifting abilities create the sense that he could be anywhere and everywhere. Unlike his reincarnations of Sesame Street or Hotel Transylvania, there is the sense that he is inherently evil and connected to Satan. Dracula is acutely aware, however, that if such evil exists, then good must be at least as powerful. And the forces of good are just as present throughout the novel as Dracula himself, taking the form of the love the characters have for one another, their cleverness and resilience, and the faith they increasingly rely on for strength and comfort. This book is often brutal, but it is never cynical; it is earnest in its belief in good over evil, and importantly, that belief never detracts from the terror that evil evokes. I’ve focused mostly on Dracula’s character thus far, so let’s talk a bit about our protagonists; in my opinion, they’re equally as important. The first we get to know is Jonathan “Get This Man A Raise” Harker, who was not only held hostage by a vampire, but escaped with his life. He is, understandably, traumatized by the encounter, arriving delirious in a Budapest hospital. Before his daring escape, the last word in his journal entry is Mina, his beloved fiancée (and shortly afterwards, wife). Wilhelmina “Mina” Harker, nee Murray, is arguably the emotional center of the novel, a character whose faith, inner strength, mercy, and perseverance helps all of the other protagonists survive. She represents all the positive traits that the undead lose. A quiet and introverted young schoolmistress, she is entirely faithful to Jonathan, and he immediately trusts her with his journal entries chronicling the terrors of Dracula’s castle. After this exchange of insurmountable trust, they’re married in the hospital. Mina’s best friend, Lucy Westenra, is a little (a lot) more outgoing. Bubbly, sweet-natured, and self-confident, she writes (impressively, without sounding like she’s bragging about it) about receiving three marriage proposals in one day. She says she’d like to marry all of them, but can only accept one – that of the wealthy young heir Arthur Holmwood, who also becomes an important character in the remainder of the novel. Lucy’s other two suitors, the adventurous American Quincey Morris, and the psychiatrist John Seward, handle the rejection beautifully. It’s no exaggeration that they could give lessons to today’s young men, and they immediately reassure Lucy. As a result, all of them remain friends. Finally, we have Professor Abraham Van Helsing, one of my favorite characters. Though Mina represents the emotional strength needed to defeat Dracula, Van Helsing represents the knowledge and cleverness (though Mina has plenty of moments of cleverness, and Van Helsing can be pretty darn emotional, becoming overwhelmed at Lucy’s funeral). He is the first one to identify that Dracula is a “nosferatu,” and that he is preying on Lucy. It is Lucy that brings these characters together – first, Mina (and by proxy, Jonathan) through her friendship, then Arthur, Dr. Seward, and Quincey via their proposals, and then Van Helsing and through her vampiric illness. It is through her illness that we see a demonstration of the love these men have for her – each gives a transfusion of blood which briefly restores her, only for it to be drained by Dracula during his nocturnal visits. Even Van Helsing donates a vast quantity of his own blood, as he comes to serve as a father figure – both to her and to Arthur, who resembles Van Helsing’s own deceased son. Throughout the book, it’s increasingly clear that he’s a paternal presence to the other characters as well. The final act of the novel is set into motion when Mina is forced to drink Dracula’s blood, and it becomes a race against time to kill him before she transforms into his undead bride. But what I find even more noteworthy is the manner in which the characters rally around Mina emotionally, and the manner in which Mina, in turn, gathers every ounce of emotional fortitude she has to be strong and cheerful. To me, it is the manner in which the characters love and support one another that makes the novel so compelling. In another novel, Quincey, Doctor Seward, and Arthur might have a bitter rivalry for Lucy’s affection, but they come to love one another as brothers. Mina becomes friends with all of the male characters, comforting them and receiving comfort in turn, and Jonathan never shows even a flash of jealousy. In the face of adversity, they become family. This makes it all the more devastating when Quincey is killed – living just long enough to see Dracula defeated and Mina’s curse lifted – and all the more meaningful when Mina and Jonathan name their child after him. One of the final images in the book takes place in the epilogue, seven years later, in which little Quincey is sitting on Van Helsing’s lap as the group reflects on their shared experiences. It is an unequivocally happy ending, devoid of any implications that Dracula will return – something we may come to expect, after being steeped in the cynical, sequel-baiting modern horror genre. But as I said before, this is not a cynical book. Not only did the main characters earn their happy ending, but Dracula, too, found release – that is, the human Dracula, who was also condemned to walk the earth as a member of the undead. One of the most touching yet overlooked aspects of the text is the moment when Dracula is impaled, and his expression before crumbling to dust is one of relief. It is at times a brutal book, but not a cruel one, and demonstrates how even one of the most famous antagonists of all time is, himself, a victim of the forces of evil. Conclusion What can writers of today learn from Dracula? A lot, it turns out.

From the many distinctive voices of the characters that intertwine to form the narrative, to the layers of dread woven into the narrative (the surface-level horror of a ghost ship arriving with a murdered crew, and the symbolic horror of lost identity), many of the novel’s lessons have proven ageless. To me, Dracula is also a study in how to make your audience care about your characters, by making your characters earnestly and wholeheartedly love each other. All were brought higher by the adventure they undertook together, arriving in a spiritually better place by the end of the book than they were when they began. The distinguished yet lonely and brokenhearted Van Helsing finds a new family, the bookish and introverted Mina proves courageous in the face of a vampire, and Jonathan, a man of insurmountable dedication, now more than ever deserves a raise. Dracula is one of the greatest horror novels of all time, but it is also an unabashed study of the redemptive and enduring power of love, and proof that soulmates are sometimes the family you build for yourself.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

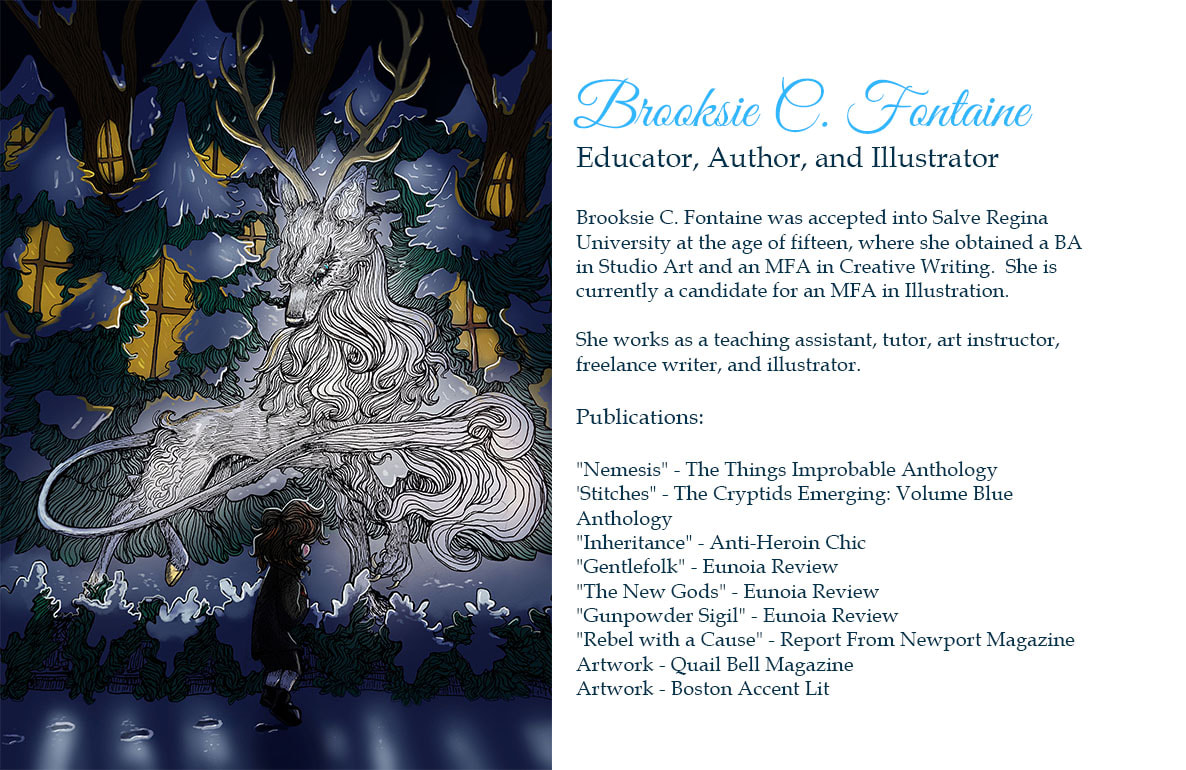

About the AuthorBrooksie C. Fontaine was accepted into college at fifteen and graduate school at nineteen. She has an MFA in English, and is currently completing a second MFA in Illustration. Archives

March 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed