|

You may have heard that titles don’t matter, and that they won’t make or break your career. Whoever told you that is either grievously uninformed or a filthy liar.

A title must do the following:

Like cover art, your title can determine whether or not anyone will actually read your book. Also like cover art, you probably shouldn’t name it like a twelve-year-old with a DeviantArt account. But how do you check off such an extensive yet vital list of criteria? Well, being the magnanimous individual that I am, I’ll tell you. Let’s take a short journey through five of my personal favorite approaches: 1. Use metaphor. Some of the most memorable and iconic titles are derived from metaphor, allegory, and simile. If you have a metaphor that encapsulates your book’s theme or tone, consider using it for your title. When done correctly, these will also provoke interest from prospective readers, as they will have to read your book to put the metaphor into context. Examples: The Catcher in the Rye, by J.D. Salinger Life of Pi, Yann Martel A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, Betty Smith 100 Years of Solitude, Gabriel García Márquez Of Mice and Men, John Steinbeck To Kill a Mockingbird, Harper Lee Lord of the Flies, William Golding 2. Ask a question. Is there a fundamental question your book is asking? (There probably should be, but that’s a topic for another day.) If so, consider presenting it to the reader from the get-go. These questions can be existential or personal, metaphorical or literal. But they should make the reader want to know the answer. Note that you can get creative about this. A question doesn’t have to be one you ask the reader, but one you provoke the reader to ask themselves. Like, “Did this author really spoil the ending with their title? I’ll have to read and find out!” As you’ll see in the titles below. Examples: Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? by Philip K. Dick Are You There, God? It’s Me, Margaret, by Judy Bloom Where’d You Go, Bernadette? by Maria Semple Skippy Dies, by Paul Murray John Dies at the End, by David Wong 3. Invoke a character’s voice. Ask yourself how your protagonist or viewpoint character would choose to title their story. Ask yourself who this person is. Are they an angsty teen? A plucky optimist? Self-conscious? Ironic? Morose? Sassy? Your viewpoint character should essentially control the tone of your novel, and the title should be reflective of such. Examples: My Big Nose and Other Natural Disasters, by Sydney Salter Everything I Never Told You, by Celeste Ng Is Everyone Hanging Out Without Me? (And Other Concerns), by Mindy Kaling Never Let Me Go, Kazuo Ishiguro 4. Utilize the setting, or a memorable place, object, or event. Is there a place, object, or event at the heart of your story? Maybe its a restaurant that is to your ensemble what the Central Perk is to the cast of Friends, a stuffed animal or piece of jewelry that serves as the story’s MacGuffin, a book that holds the secrets to the protagonist’s identity. Or maybe it just, for one reason or another, perfectly encapsulates the tone and philosophy of your story. I seem to be partial to this one, because it’s how I chose to name three of my novels: An Optimist’s Guide to the Afterlife (named after a book handed out to the recently deceased), General Tso’s Chicken From Outer Space (named after a Chinese food restaurant in a UFO hotspot town), and Diner at the End of the World (named after a diner frequented by Eldritch Horrors.) Examples: ‘Salem’s Lot, by Stephen King The Road, by Cormac McCarthy The Restaurant at the End of the Universe, by Douglas Adams Jurassic Park, by Michael Crichton Good Omens, by Neil Gaiman and Terry Pratchett The Lord of the Rings, by J.R.R. Tolkien 5. Introduce the protagonists (but get creative about it.) In ye olden times, an opulence of great literature popped up that was named after specific characters. Think Anna Karenina, Oliver Twist, David Copperfield, Don Quixote, The Great Gatsby, and Jane Eyre. You can still do this–lots of authors still do, and it works great if you have a particular cool or quirky name–but in an already saturated market, it’s probably a good idea to put a twist on it. I’ve observed three ways to go about this. First, you can introduce the main character and major conflict/theme of your story. Examples: Simon Vs. the Homo Sapiens Agenda, by Becky Albertalli Aristotle and Dante Discover the Secrets of the Universe, by Benjamin Alire Sáenz The Miseducation of Cameron Post, Emily M. Danforth Approach number two: introduce the readers to the group of people your story is about. Examples: The Help, by Kathryn Stockett American Gods, by Neil Gaiman The Twelve Tribes of Hattie, by Ayana Mathis The Vacationers, by Emma Straus Crazy Rich Asians, by Kevin Kwan And approche trois, name the title of a main character, particularly if it’s memorable and plays a large part in the story. Examples: The Giver, by Lois Lowry The Obituary Writer, by Ann Hood The Beekeeper’s Apprentice, by Laurie R. King The Hobbit, by J.R.R. Tolkien The Martian, by Andy Weir These are just a few of my favorite methods of naming stories! To my followers, I invite you to add more, and to share your own favorite titles. Other sources: How to Come Up With the Perfect Title For Your Novel How to Choose Your Novel’s Title: Let Me Count 5 Ways 7 Tips to Land the Perfect Title For Your Novel How to Find Good Titles For Your Novel How to Name Your First Novel How to Title Your Novel I hope this helps, and happy writing! <3

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

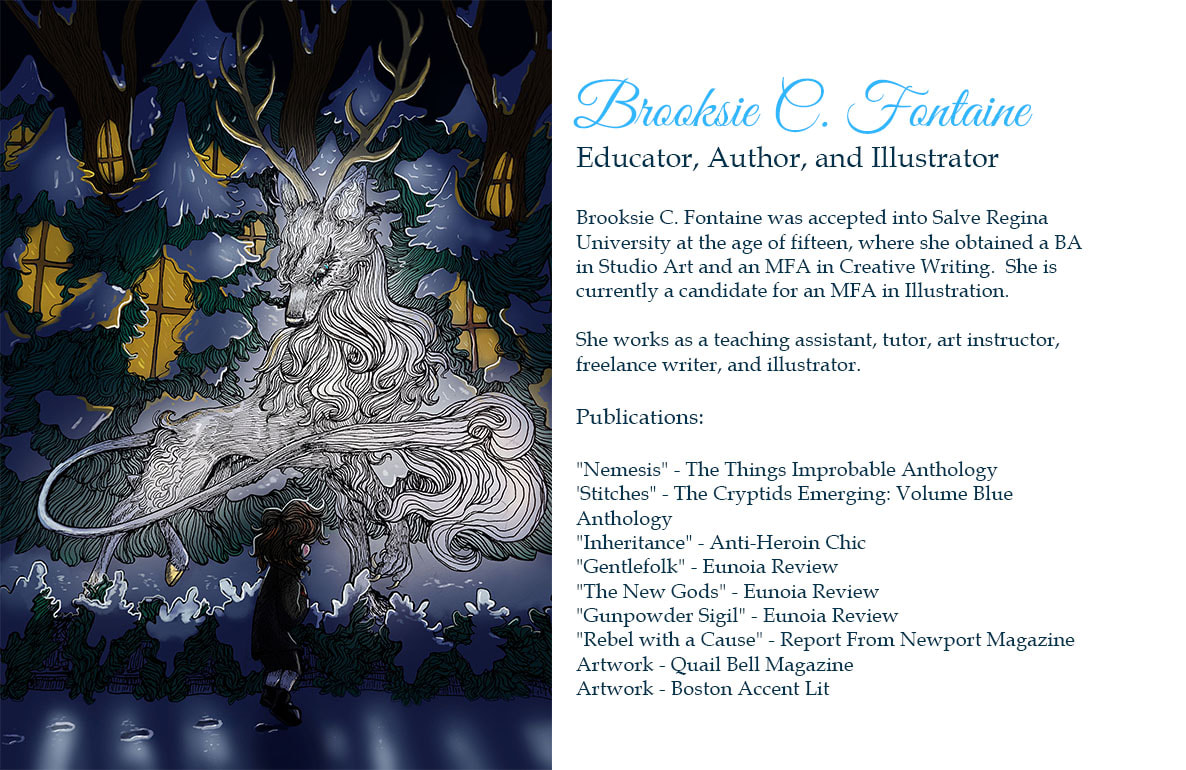

About the AuthorBrooksie C. Fontaine was accepted into college at fifteen and graduate school at nineteen. She has an MFA in English, and is currently completing a second MFA in Illustration. Archives

March 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed